Who Is Big Brother? A Reader’s Guide to George Orwell (Guest: D.J. Taylor)

Download MP3What's the time? It's time to get ill. What's the time? It's time to get ill. So what's the time?

Intro:It's time to get

Tim Benson:ill. Show lost the time. Show lost the time. Hello, everybody, and welcome to the Illiteracy podcast. I'm your host, Tim Benson, a senior policy analyst at the Heartland Institute, a national free market think tank.

Tim Benson:We're probably around episode a 150 or so. Sorry about that. Never really remember the episode numbers. My apologies. But, point being, we're not a very new podcast anymore.

Tim Benson:But, for those of you just tuning in for the first time, basically, what we do here in the podcast is I invite an author on to discuss a book of theirs that's been newly published or recently published on something or someone or some idea, some event, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera, we've, we think you guys would like to hear a conversation about. And then hopefully at the end of the podcast, you, go ahead and give the, purchase the book yourself and give it a read. So if you like this podcast, please consider giving your literacy a 5 star review at Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to this show and also by sharing with your friends because that's the best way to support programming like this. And my guest today is mister DJ Taylor, and mister Taylor is a writer and critic with a career spanning over 35 years. His criticism has appeared in outlets such as The Spectator, literary review, The Guardian, The Independent, The Daily Telegraph, and The New Statesman among others.

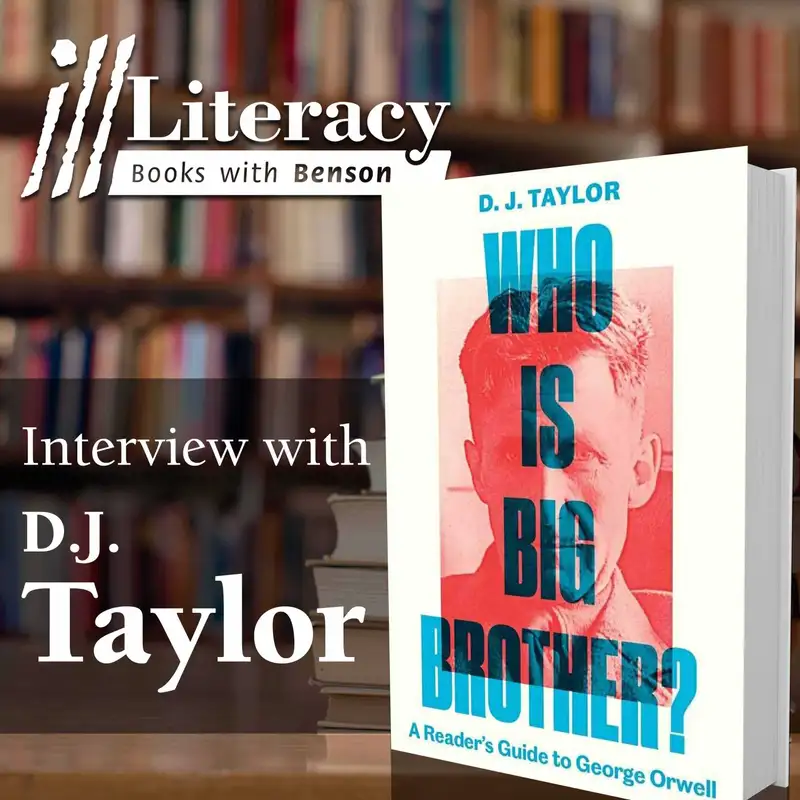

Tim Benson:He's the author of 12 novels and numerous works of nonfiction, including After the War, the novel in England since 1945, Thackeray. On the Corinthian Spirit, the Decline of Amateurism in Sport, Bright Young People, The Rise and Fall of the Generation, 1918 to 1940, The Prose Factory, Literary Life in England Since 1918, Lost Girls, Love, War, and Literature, 1939 to 1951, and Orwell, the life. And he is here to discuss his latest book or 2 latest books, actually, I should say. Orwell, the new life, which was published last May by Pegasus Books. And Who is Big Brother, A Reader's Guide to George Orwell, which was published, just a few days ago, I think, by Yale University Press.

Tim Benson:So, mister Taylor, thank you so so much for coming on the podcast. I do appreciate it.

D.J. Taylor:It's great to be here, Tim. And do please call me David. The DJ was adopted many, many years ago. There were dozens of people writing in Britain called David Taylor, and I used to get somebody on the mail or something. Now, of course, you see there are DJ Taylors.

Tim Benson:You know, they're just jockeying. Yeah. Yeah. Exactly. Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. I was gonna say that you could just transition right into, you know, just jockeying yourself if you wanna go to the clubs and DJ Taylor. Yeah.

D.J. Taylor:I'm a music fan. I I can handle that. Yeah. I was interested, actually, you you were you were telling your, your listeners the the the periodicals I write for. Increasingly, I seem to turn up in American, publications.

D.J. Taylor:I don't know what it is, but I I I'm, yeah, I'm I'm doing a lot of stuff these days with The Wall Street Journal and New Criterion, the DC and Sandler and things like that, which is great. III love writing for America.

Tim Benson:All, all publications I, subscribe to. So

D.J. Taylor:Well, it's a funny thing you see, but in the large majority of cases, the American publications pay more than their British equivalents. It's, you know, it's it's a great thing to be involved with the stateside literacy. And so I'm I'm very keen on this. Anyway, do go do go ahead.

Tim Benson:Yeah. No problem. Alright. So I I guess we get to so I guess first question is, before we get to the books themselves. So you spent a lot of your life writing about George Orwell.

Tim Benson:How did, how did you get into Orwell, and how did you how and why did you decide that this is a a man and, his literary corpus is something you wanted to, explore and and and deal with over, you know, such a long period.

D.J. Taylor:It's interesting because I found that most people in the UK, come to Orwell through the school curriculum. So they're compelled to read Animal Farm in 1984 in teenage years. And I I get the impression this is quite similar, in America because I was, I was doing some events in Boston last fall and, and Rhode Island, places like that. And out of interest, I just started the gigs by saying, could you put your hand up if you read 1984 and the forest, the fans would go up? And then I and and the same with with Animal Farm, which is great, you know, from the from the barker's point of view, because you're starting the the bar's raised.

D.J. Taylor:Everybody knows what you're talking about. They've been there. They have the vestiges. But in fact, I got into Orwell quite by chance because the very small collection, of books on my mother's bookshelf included a paperback copy of his second novel, A Clergyman's Daughter, which is not very well known. And, even Orwell nuts would probably concede that it's not his greatest ever work of fiction.

D.J. Taylor:And it's it's about this, it's about the clergyman's daughter living in rural Suffolk who loses her memory and ends up sort of trampling the streets and picking hops down in Kent and having all kinds of adventures and then being returned to her father's rectory. And, for some reason, at the age of, I don't know, 12 or 13, this book spoke to me in a way that, no, it was the first grown up novel that I read, if you know what I mean. And, the the sensation that I had was exactly the same as where as which Orwell says that he had when he first read the works of Henry Miller. He read Miller's Tropic of Cancer in 1936, and he said,

Tim Benson:And that's a book that definitely is not on school curriculum.

D.J. Taylor:No. I just don't see it. It's not even now. No. You're always very impressed by this, you know, by by Miller's use of the vernacular and the stream of consciousness and getting inside the head of the ordinary person.

D.J. Taylor:And he said he thought that it was as if Miller had written the book for him. He knows all about me. He knows I'm here. And for some reason, I have exactly the sensation with The Clergyman's Daughter. I found this I found it immediate direct.

D.J. Taylor:I found that, it was like a bullet coming back from across time. You know, just and it just been written for me. There was 1 copy of that book in the world, and I'd happened to stumble upon it, and it was my secret. And and it had a kind of and, and so after that, I read everything of Orwell I could find, and it all stacked up. You know, I never found a piece of Orwell's writing that I didn't think had something in it that appealed to me, that told me something I didn't know, that introduced me to a writer that I hadn't previously come across.

D.J. Taylor:And all this is quite apart from, you know, the 2 great dystopian classics, Animal Farm in 1984, whose merits I, you know, would would consider would would allow and proselytize on behalf of. But, I suppose I came to Orwell through the other stuff way, through his 19 thirties novels, which are not as well known as the big 2, although you can see the seeds of the big 2 in them, you know, because in some ways, everything that Orwell wrote is leading up to those great works of the late 19 forties.

Tim Benson:But Sure. But could you say that those those early novels are sort of more truer? I mean, 1989 and or excuse me, 1984 and Animal Farm are sort of unique in a way in their, in the Orwell corpus. I mean, so the the earlier writings are a bit.

D.J. Taylor:You're right. You're right. The the the the last 2 novels are dystopia. You know? They're setting them out.

D.J. Taylor:1 1 is a sort of satire of the Soviet revolution done in the form of a fairy tale, And the other is a dystopia, but it's, it's early readers. I think what what, the effect that it has on it had on its early readers, especially in the UK in 1949, was exacerbated by the fact it was obviously their world. You know? It was it was it was bomb damaged London. So it Yeah.

D.J. Taylor:It's a work of realism in a way, which has just been twisted out of kilter. But you're quite right. The 4 thirties novels are what we would call works of realism. I mean, they're set in recognizable English environments. They're they're quite old fashioned in their treatment.

D.J. Taylor:They're not you know, this 19 thirties was the age of literary modernism. It's the age in America of Jondos Passos and people like that. He

Tim Benson:Right. Right.

D.J. Taylor:Isn't like that at all. You know, he's he's borrowing he's using very elderly literary models, and they're quite old fashioned books. But, you know, you can't help yourself. I liked them when I was 15, 16. Yeah.

D.J. Taylor:They were my kind of books. And I I'm

Tim Benson:know. Oh, so I was I was just gonna say, I don't I don't know. I mean, I'm not really sure if they're still on the curriculum anymore. It seems like curriculum everywhere has just been sort of dumbed down a lot. But, I mean, they were I think we read them my freshman freshman year honors English class, both 1984 and and animal farm.

Tim Benson:But I don't know if that's it's common, but I'm 40 years old now. So this was, you know, 20 years ago at least, 3rd or 25 years ago. But, I don't know if that's, I mean, I went to a Catholic school, and my English teacher, I remember, I guess he was a very hard line anti communist because we also read A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich the same year. So I don't know if that was just his specs special curricular or if that's something that was more general. But it yeah.

Tim Benson:But, I mean, even if not, you know, so much of 1984 especially, has become ingrained in the vernacular, you know, doublethink and the thought police and thoughtcrime and newspeak and 2 +2 equals 5, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. So, you know, even people who haven't read 1984, I mean, I feel like have, like, a general Well, this is the thing. This is. You know?

D.J. Taylor:This is the thing. You see, he's 1 of those writers, and there are very few of them, you know, 2 or 3 each century who's thinking, who thought process, and who's big sort of slow big ideas enter the consciousness that's secondhand of people who may not have ever read the books. And so, you know, there's a there's a, you know, there's the big brother television series. There's another TV series in the UK called Room 101 where you go and and it's completely trivial. You know, in in in in 1984, Room 101 is the thing you fear.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. It might have been a

D.J. Taylor:worst nightmare I should imagine is that the the UK television program is just, oh, I don't like frogs. It's it's it's it's completely trivial in in some way. But so that's the thing. So you're you're starting and as Orl himself said, you know, in the 19 thirties, if a muse if a comedian had gone on stage in a British music hall and imitated 1 of Dickens' characters, people probably would have known who he was doing even if they hadn't read Dickens because the characters are so ingrained in in in the public's mental landscape. And the same is is true, I think, now with Orwell.

D.J. Taylor:You're it it's it's, as I say, it's very useful for people writing about Orwell because you're starting with a broad corpus of knowledge already. I mean, if you if you write a biography of somebody fairly obscure, you spend the first 10 minutes of any talk you're doing explaining who they were and what their relevance is. You don't have to do that with all. You go straight in, and he's the man. You know?

D.J. Taylor:You're there already. I mean, this is why we're having this conversation. You you know about him to begin with.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Sure. So, yeah. So the book, it's of the or or the new the new life, biography. So you wrote Orwell, the life that, like, came out 20 years ago, 21 years ago, 2.2, 003.

Tim Benson:Yeah. 2003. Mhmm. So, just for everybody's knowledge, so the new life is not just like a revised and updated version of the life. It's a completely, basically, you wrote an entire new text for this biography.

D.J. Taylor:I did. And, rather than simply, you know, sort of, inserting bits of new material, I I started again from scratch. I looked at all my old interview notes. I looked at all the new material that had come along of which there was a great deal. I mean, this was really the justification for writing the new book was that, several there were some really fascinating and quite extensive new manuscript sources came along.

D.J. Taylor:There were 2 big collections of letters. I discovered, Wheaton College in Illinois, which has the Malcolm Muggeridge archive, turned up some cracking stuff that we didn't know was there before, you know, dating the 19 fifties when when Malcolm Muggeridge had thought he might be Orwell's first biographer and accumulated all kinds of ideas. So there was all kinds of new material. So, as I say, rather than simply inserting it all into the original text, I sat down and started again from scratch. And the result is substantially longer book, I'm afraid.

D.J. Taylor:It's 600 pages where the original 1 was 450. But I still I still don't think that, I overdid it because there was so much material, and it's Orwell. You know? It's Sure. And it could have been a 1, 000 pages, but I I stopped myself.

D.J. Taylor:So, yes, it is it is I would I would sort of contend that it's a new book rather than some new revised version of the of the old 1.

Tim Benson:Was it difficult to rewrite it after writing it once? Because you've already written the book once, so it feels like it would be hard to write it again because you've generally already said what you wanted to say to begin with. Like, I in my previous life, I had a job. 1 of my previous jobs was, like, ghost writing op eds for politicians. And, so I would get, like, a thing, like, okay.

Tim Benson:Write an op ed for someone so on this topic. And then I'd get a, you know, prompt, okay, write basically on the same topic, an op ed for a different person. And it was like, well, shit. I just wrote this op ed. And I said every I mean, I basically had it formed and everything perfectly how I wanted to.

Tim Benson:And now I have to rewrite it and write it entirely differently so that I'm not plagiarizing myself. And, you know I do really

D.J. Taylor:have a problem, actually, because 1 of the techniques I used in the original book was where I had a a theme that I was interested in. Sometimes they didn't fit into standard biographical narratives. So for example, I was interested in Orwell's voice, of which there's no known recording, although there may there may be 1. We're not quite sure. Orwell's great phobia, which was the rats.

D.J. Taylor:You know, Orwell is completely obsessed by rats from the very earliest time, and then they turn up as the great horror motif in 1984 in Winston's torture. But, the I discovered that, as I say, they didn't fit into the standard biographical narratives because you can't just stop in the middle of a chapter and say, oh, by the way, Orwell was obsessed with rats and then write 4 pages about this. So I did a series of little mini essays in the first book where I examined some of those themes. And then, of course, by the time I got to the second book, I got a a load a whole lot more areas where I thought 1 could do this that hadn't necessarily been covered in the first book. So I wrote sort of essays.

D.J. Taylor:I'm for example, Orwell's view of the past, Orwell's view of the working classes, Orwell's Orwell's you know, I wrote a little chapter called Orwell's enemies about, the small but, you know, quite interesting corpus of people who didn't like him for various reasons. And Orwell is so often sort of sanctified and beatified, by his fan, by his admirers that it's it's sometimes very interesting to look at the people who didn't like him and see the reasons why they thought he brought them up the wrong way. So Mhmm. It was, to an extent I I was very conscious of not wanting to bore myself all the readers by going over old ground, but virtually everywhere I looked, there was something new to say and something substantial. The only I suppose the only areas where there wasn't a very great deal of new material and it was difficult was those early formative years because you see I mean, he's born in 1903, so there's nobody left alive who know knew him from the first sort of 20, even 30 years of his life.

D.J. Taylor:And you really are you're struggling to get new perspectives. So that wasn't, that was slightly but even so, you know, I was finding out new stuff. I mean, I discovered, for example, in a terrifically circuitous way, you know, through the descendants of people who were there at the time. I discovered that when Orwell came back from Burma in 1927 when he stopped working for the imperial police force in the British empire, he came back with an engagement ring, you know, which he wants to present to the teenage sweetheart he'd left behind him. Now that's that's really interesting because that gives him a motive.

D.J. Taylor:And it also it adds a very interesting gloss on you know, people have biographers always say, why did Orwell come back from Burma? You know, he must have come back because he hated British imperialism, and he wanted to, you know, to smite smite the Raj that he'd served and so forth. But in fact, Orwell came back from Burma on a medical certificate. He was ill. He'd been sent home because he was seriously ill with dengue fever, which is a tick borne virus that you get in the tropics.

D.J. Taylor:And he also came home with an engagement ring. Now I I said to myself, he came if he came home

Tim Benson:Came home for a girl.

D.J. Taylor:Exactly. He came home. But, see, what and she turned him down. But what would have happened if the girl had said yes? Well, I think because it was the only form of, of of salary available, I think they'd have got married and gone back to Burma.

D.J. Taylor:I think Orte would have carried on serving in the imperial police had she said yes. So so that's what I mean about significant new things even from the early days coming up. And then, of course, when you got into get into the 19 thirties, there are 2 enormous new caches of letters to to suffer girlfriends from the early 19 thirties, which really do open up the field and tell you more things about him. A lot of them are quite fundamental to biography, you know, just things like where he was. I mean, a lot of Orwell's life is very difficult to to plan out in the early 19 thirties, not simply not knowing where he was, what he was doing, and and this gives you it's much easier.

D.J. Taylor:It was much easier with some of this new material to map out the territory a bit more, if you see what means. So so by the time I got to the 19 thirties, it was a whole new deal. And in fact, the 19 thirties section of the book is about twice as long as the original. There was so much new material and so many new perspectives from from people I came you know, people I turned up.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Or the Sorry. I was gonna say, yeah. If she would have said yes, then they go back to Burma, then, you know, maybe he writes, in his spare time or whatever when he can manage. But, because he you said in the biography that, you know, he knew from a very early age he wanted to be a writer, like, from the age of, like, 5 or 6, which must have been nice to have that sort of, you know, that sort of, clarity on what your role's gonna be.

Tim Benson:But, you know, obviously, if he goes back to Burma, even if he still writes, it's gonna be he's gonna be a very different writer and a very different person than, you know, what he turned out to be.

D.J. Taylor:And the other the other thing too was the, and I suppose which which which I think probably gives the book, if not intentionally, a certain poignancy. As you see, when I wrote the original when I started researching the original book, which is the end of the last century, you know, it's a quarter of a century ago, and there were still any number of people around who've known him because he'd only been dead 50 years. So there are plenty of there are plenty of hail 80 year olds who knew him in literally London in the 19 forties who were anxious to say what they had to say. And it was very interesting, you know, to talk to them. They're all dead.

D.J. Taylor:All the people all the people who knew him when he lived in Southwell in on the Suffolk coast in the 19 thirties, a few of who were still alive in the in the early 2 they're all dead as well. In fact, I sat down, with Orwell's adopted son, Richard Blair, not very long ago, and we worked out that there were only 7 people left in the world who can remember him.

Tim Benson:Does his son actually, thinking of that because his son, his adopted son, obviously, Orwell died when his son was very young, I think 4 or 5 years old.

D.J. Taylor:5 and a half. Yeah.

Tim Benson:5 and a half? Mhmm. Does he have any recollection of his father at all? You know? I mean

D.J. Taylor:He has he has powerful recollections. Yes. Because you see his early childhood, Orwell's, Richard's Richard's mother, Eilid, died when he was a year old, 1945 in tragic circumstances. Orwell resolved to bring Richard up himself, you know, which I always think is a point in his favor because he could have gone straight back to the adoption agency, you know, and then the services were being, you know, being an adopted child. And, and so Richard's early years were spent on the remote Hebridean island of Jura where his father was writing 1984, and he has vivid memories of this.

D.J. Taylor:And, the thing is, though, of course, especially with his father being in hospital for the last year of his life when Richard didn't get to see him much is that, obviously, Richard remembers what he remembers, and he forgets what he forgets. And, I mean, I've known I've known Richard for for many years, and I'm I'm always kind of been I'm always informally trying to prod him to remember other stuff. You know? And and it's very, very rare that he does. In fact, he did not long ago, he did he remembered something new.

D.J. Taylor:He remembered being, before they went to Jura, they lived in a flat in Islington in North London, when Richard was about sort of 2 going on 3. And and Richard remembered, putting his finger in the door buzzer and getting a minor electric shock and all while being very cross and protective of him and telling him it was something he mustn't do. And he and then he remembered playing with his father's tools, you know, his chisels and his hammers. And so, again, being ticked off and sort of told that these were dangerous. But it it's not very often that that happens.

D.J. Taylor:So, so tracking and I was I was very fortunate because I I say, Richard, you know, is is still, you know, heartily with us and very he was very involved with the project. In fact, the book dedicated to him, all of life. But I also managed to turn up, I managed to turn up a woman called Sarah Cox, who was the daughter of the nanny that Orwell engaged to look after Richard in 1946. And so she remembered coming to Jura as a girl of 9, you know, and Orwell sort of driving her up to the farmhouse and sort of talking to her about the island. And that's, you know, to have those and I and I turned up an old gentleman of 93 who'd known him in Southwell in the 19 thirties.

D.J. Taylor:So being able to tap these sources for what I'm afraid is the last time you know, by the next time somebody writes another autobiography, there'll probably be no 1.

Tim Benson:0, sure.

D.J. Taylor:That that really is when we lose the last, you know, connection, the last living connection with a man who's been dead 74 and a half years. It it that that's when it that's when it it does start getting very difficult. So I was very lucky to get him just at the end of the of that that line.

Tim Benson:Yeah. I, I see what you mean, but, you know, he can only remember what he can remember. Something about only child, because I'm an only child, something I've noticed. The thing about it is, like, you are the only 1 that really understands have siblings have siblings I've noticed this with, like, my, like, my aunts and uncles and, like, you know, when we get together as a family or something like that. And, you know, an aunt or uncle say, hey.

Tim Benson:Do you remember when we were growing up that this happened or blah blah blah or this or something? And then 1 of the other siblings will, like, be like, oh, I completely forgotten about that. But, yeah, now now that you say that, I remember blah blah blah blah blah. But, but if you're, you know, if you don't have anyone there to trigger, that memory, you can just sort of be, you know, lost to No.

D.J. Taylor:I agree. I mean, Richard Richard's story, it's quite a story because, you know, he he was adopted. So he's 5 and a half when his father died. By this time, Orwell had got married again to Sonia, his second wife. And Sonia made it pretty Sonia was a lot, like, younger than than Orwell, and she made it pretty clear that she didn't want to have anything to do with Richard's upbringing.

D.J. Taylor:So he was brought up by an aunt, by Orwell's sister, Avril. And Avril didn't tell him that he was adopted until he was 12 or 13 just as he was about to go off to school. And he said, there you are. So, oh, by the way, you know, he wasn't actually your your, your biological father. And I remember asking Richard, you know, what on earth did that effect did that have on him as a boy of 13 to suddenly find this out?

D.J. Taylor:And Richard was was very matter of fact and said that so much had happened to him in his short life by that point. You know, there'd be so many changes of scene and changes of people looking after him that he just accepted it. He thought,

Tim Benson:oh, well, he

D.J. Taylor:was my father. But It's just natural. Yeah. Yeah. And then off we go again.

D.J. Taylor:And so, I think you needed you would have needed a a substantial amount of resilience to be able to get through that. I mean, you know, some people would just have fallen apart with that that kind of revelation. So I think all that was very admirable on his part. And in fact, it all it all worked out wonderfully because in Orwell's letters from the late 19 forties, there are lots of references to Richard and, you know, all all observed him closely and said things like, you know, I don't think he's gonna be very academic, but he's he's got a practical side, and I'd love it if he became a farmer. And in fact, Richard did become a farmer and worked for Massey Ferguson, the agricultural people, and then, you know, made a whole life for himself before, you know, the the before he had any kind of access to the to the huge amounts of money that his father left him.

D.J. Taylor:So I think Aude would have liked that. Aude would have been proud of that. I think it was a good thing. Yeah.

Tim Benson:That's great. So, let's go back, I guess, to the beginning a little bit of his life because you wrote about this in the, in Who is Big Brother. But so Orwell was born in 1903, and he's he's not born in England. He's born, in India, in Bengal. And, you say that the date and the location of his birth are sort of vitally important to the view he came to take of the world and the kind of person, he imagined himself to be.

Tim Benson:So he's an Edwardian. Yeah. And still and and even then, the the Victorian era itself left a crucial impact on him. And I guess that's not surprising. It's sort of, I guess, the way that the the sixties sort of have left the, you know, an impact on the people born in the 19 seventies, 19 eighties, etcetera, you know, that sort of thing.

Tim Benson:So, could you talk about that a little bit

D.J. Taylor:just to I think that's fair that's a very apt comparison, actually. Yeah. I mean, so was born in 1903. And despite his left wing the left wing political views that he there he then came by, it's almost his entire outlook was that was that of what they'll say, an Edwardian gentleman, if you know what I mean. And it's significant to me that some of his closest friendships were made with people who came from that kind of group.

D.J. Taylor:Mhmm. So, for example, he was a great friend of the the English novelist, Anthony Powell, whose father had been a lieutenant colonel. They both went to Eton. The Eton thing, the English public school thing is vitally important for understanding Orwell because he was such a a chap, if you know what what that means in in English. English gentleman.

D.J. Taylor:Sure. And he could never and he could never 1 of the things is that his, you know, his view of the past is this impossibly kind of romantic thing about sort of round heads and cavaliers and peasants in their huts and noblemen in their mansions.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. Most people wouldn't think Orwell was a you know, if you think Orwell, you know, the casual person, you wouldn't think, oh, that, you know, he's a romantic. No.

D.J. Taylor:He's a drama. In terms of English history in terms of English history, he is thoroughly romantic. You're quite right. And in fact, it's fascinating because he was once in the early 19 thirties, he worked as a private tutor to some small boys. And, he once said to them that if he'd been alive in 17th century and could have fought in the English Civil War, he'd have been a can he would have been around it because the Puritans were such dreary people.

D.J. Taylor:And, of course, Orwell, in terms of his political, you know, views, he is absolutely a a Puritan and around him. But, no, no, they were they were too dreary for him. So you're right. That's that's the fundamental grounding that followed him sort of followed him through his life, and it comes up. Again, a friend of his once said that he was conservative in everything except politics.

D.J. Taylor:And I have to agree with that because, you know, he's so, he was capable of writing the most sort of radical radical nostrums to solve English for political problems, but he still goes back and eats an awardee and high tea with a big, you know Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. What was, is Yeah. Was it Cyril Connolly Cyril Connolly, his editor, has said something like, he was a revolutionary in love with 1910 or something.

D.J. Taylor:Yes. And and and preserve all those attitude. Yeah. So it's it's, you can't you you can't ignore that Edwardian upbringing. And, you know, his whole you see, the the whole tradition of this family on on both sides was, you know, that of I mean, his imperial service.

D.J. Taylor:His father was an Indian and worked as a civil servant in India. His mother's family were birth were were were French, but had had made a living in Burma built as boat builders and Mhmm. Local administrators. So there's this tradition of service on either side, which is why he fitted so well into that sort of early 20th century imperial and then post imperial culture. And this, of course, because he'd had this this 2 kind of barbs, if you like, his attitude to conventional left wing ideas of empire and colonialism because he'd seen it at first hand, you know, how how colonial administration works.

D.J. Taylor:So although he sympathized with the the native populations whom he was had suppressed as a young man, when he got older and he read the standard left wing line on imperialism, he he was you know, he still then quite often moved to fury because he said, these people are sitting in armchairs in England and don't know what it's like out there. I mean, he once said he once said that in India, run along the lines advocated by the Bloomsbury novelist, EM Forster, would last about a fortnight because no 1 would have any idea about practical administration and how things how things operate. And so he said that perspective is very important because it gives him a kind of pragmatism. It gives him a kind of objectivity that a lot of left wing political commentators don't have.

Tim Benson:Yeah. He was definitely not a fan of the socialist intellectual. Wait a minute. No. And, but, what are the I'll just say, I think it's, you know, people I know there's this tendency or people on the right where they find try to find, like, sort of the, crypto right winger in in Orwell.

Tim Benson:But I think I've I mean, just looking at the guy in general, I think it's pretty fairly odd, like, personality wise that he has a very strong small c conservative, or small c, the the the very English traditional conservative, sort of reminds me, you know that song, by the Kinks, the, the Village Green Preservation Society? Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yes.

Tim Benson:You know?

D.J. Taylor:The Kinks. Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. You know, the skyscraper condominium affiliates, you know, God Save Tutor Houses, antique tables, and billiards, you know, and all that sort of stuff. Like, I mean, that song seemed that seems to be Orwell very much.

D.J. Taylor:Oh, I think so. Yes. No. That and then absolute that Englishness too, that, yeah, bygone, That kind of it's always an allergy for a lost life. You know?

D.J. Taylor:In fact, the 1 of his 1 of my favorite novels of his is Coming Up For Air written in 1939, which is a kind of war is coming novel. It's written on the cusp of the 2nd World War. And it's just an elegiac lament for the ox Oxfordshire of his childhood, you know, and sort of and the hero goes back and tries to find a cart pool that he remembers there from 19 o you know, from the from the prewar era, and it's now a municipal rubbish dump. And and everything has been built up, and the houses are encroaching. And and, you know, the the modern world has dumped itself on lower Benfield where the the hero comes from, and it's all terribly sad and elegiac.

D.J. Taylor:So, yeah, I agree. Yes. I agree with you there. He's a great sort of, you know, he's a great sort of elgist of a lost England. Mhmm.

Tim Benson:And, you know, you said, you know, his friend and his sort of peer groups all come from the same sort of circle, middle class, upper middle class circle. But he really identified with the working class, and, and he had a, I guess, maybe disdain is the right word or a dislike about, many things about middle class life and the petite and the the petite bourgeois and all that. And, you know, I think it was v s Pritchett has that line that, you know, regarding Orwell and his his affinity for the working classes that, you know, he went native in his own country when he was yeah. Yeah. When he was in the late twenties and early thirties when he was going you know, doing the road to Weidken Pier and all that.

Tim Benson:And, talk a little, about that, his his affinity for the working class or working class people.

D.J. Taylor:Well, I think it was an let's qualify this and say it was an attempt to gain an affinity

Tim Benson:with Right.

D.J. Taylor:Because the the hilarious thing, of course, about and and you're right. I mean, Pritchard Pritchard, when he examined I mean, Orwell, when he decided that he wanted to be a writer in the late 19 twenties, did go off on the he he sort of, disguised himself as a tramp and went and stayed in casual wards. He went to Paris and worked as a did washing up in hotels and restaurants. And he did, you know, he associated what with what he called the lowest of the low. And, and he he did.

D.J. Taylor:There was this tremendous, you know, the the EM Forster's thing, only connect. Orwell wanted very much to connect with with those people and tried very hard and got on well with them and was, you know, was welcomed by them and and got on very well with the, you know, the east the London East Enders that he picked up with in Kent in the early 19 thirties, but he could never be accepted by them because they knew him for what he was. You know, they knew he was a toff for sure what he wasn't. And then and and some of the stories that emerge from, you know, these attempts are absolutely hilarious. And I I used to know, I was talking earlier about 20 years ago, there were still quite a few survivors of those those times left.

D.J. Taylor:And I I remember having a conversation with a novelist called Peter Van Sittert, whom Orwell had employed, as a young writer when he worked on the the the weekly magazine tribune in the 19 forties. And Orwell once took Peter Van Sitter to a pub in Fleet Street in London and sat him down and and lectured him, you know, and sort of said, the thing is, Peter, that with an accent like yours and wearing a tie like the 1 you're wearing, you will never be accepted by the working classes as 1 of themselves. And Van Sittet didn't want to be accepted by the work. And so and so and as he was kind of glaring at this, the the pub landlord, you know, the barman came over and said, can I get you can you get some more drinks? And then he looked at he looked at and said, Peter?

D.J. Taylor:Then he looked at Orwell and said, sir? He wrote Orwell was a gent, you see. So all Orwell's attempts to kind of and and he would do this though. He had kept the he had colleagues. When he worked at the BBC, he once there was a co a colleague of his called John Morris that he took to a pub.

D.J. Taylor:You know, he said, let's go go to a pub.

Tim Benson:Hello?

D.J. Taylor:Hello?

Tim Benson:Are you back?

D.J. Taylor:Oh, sorry. You disappeared disappeared a moment.

Tim Benson:Yeah. You did too. I don't know. I don't know whether it was my end or your end. Sorry about that.

D.J. Taylor:So Orwell took his younger colleague to the pub and and to which he said, what will you have? And so this this chap didn't even drink. So he said, oh, I suppose I'll have a pint of beer. And Orwell said, oh, you've given yourself away there there. You know?

D.J. Taylor:Bitter. Right. Or a working class man would say a pint of bitter. Yeah. And Allwell's Pollock was completely bemused.

D.J. Taylor:You know, he didn't like going to pubs. He didn't want to drink beer. Why did he have to be seen to have this badge of affinity? So Orwell, I think, had and and then, again, Orwell's friend Richard Rees, has has stories of him in the day in the 19 forties going to drink in a big working class pub in Islington and and sort of wandering around with a a benign smile on his face, but not really managing to connect with anybody and looking horribly out of place, you know, not looking as if he belonged there because he's different kind of person from the rest of the people in the pub. So so the attempts to connect, I think, were pretty much doomed to failure because he was always spotted for what he was.

D.J. Taylor:You know? He didn't Sure. He He he was he was an upper class man slumming, basically, working class. Right. That's a

Tim Benson:good word for it, slumming.

D.J. Taylor:Yeah.

Tim Benson:Alright. So moving on a little bit, I guess, more to the political Orwell. And I guess let's talk about, Spain. So, I mean, he's he's already a socialist by the time he, goes to Spain in 19

D.J. Taylor:Well, a nascent. AAA nascent. A nascent thing is proper word.

Tim Benson:But yeah. But so how does his experience in Spain, politicize him in a way that say English Socialism hadn't to that point?

D.J. Taylor:Well, well, this is very interesting. I I just because in the last 24 hours, I've come across a couple of responses to Orwell's time in Spain that are quite fascinating. 1 of them from the right, 1 of them from the left, but you'll you'll see their pertinence in a moment. So Orwell's view was that he gets to revolutionary Barcelona at the end of 1936, and he sees something that he's never seen before, which he reckons is a society where they had managed to bring in some form of equality and fraternity and freedom. And everybody there didn't seem to be a middle class and even, you know, the wait the waiters and the bootblacks called you you instead of sir.

D.J. Taylor:And and Orwell thought that he'd stumble. He he wrote to Sir O'Connell and said, I've seen wonderful things. You know? And and and this to me was the galvanizing, moment for him where he believed that, you know, egality, fraternity, liberty were all achievable. Now, interestingly, I there was a review of my my new book, Who is Big Brother, in, an American publication, Law and Liberty, just yesterday, where the reviewers said yeah.

D.J. Taylor:That's a great point. Yeah. And the reviewer said, fortunately, he very much liked the book, which I was grateful for, but he said that the awful thing was that the the conditions that Orwell thought that he liked when he got to Spain were totalitarian. You know, it was unlike something in Cambodia and and and frightful, and there's sort of this basic equality did nobody any good at all. And I've just read a review today of a book about, the Spanish civil war and English responses to it by the very distinguished historian of Spain, professor Peter Preston, who accuses all of dishonesty, and, you know, misrepresenting the left in Spain.

D.J. Taylor:And in fact

Tim Benson:Hello? Yeah. Thank you for having me.

D.J. Taylor:A bit of a mess. So so the so the left the left wing view of Orwell's time in Spain is also harshly critical of him as well. For, you know, the the Orwell's problem being that he joined a very sort of Trotsky splinter group called the POUM and had no real idea of what was going on in other parts of Spain. So it's possible to sort of get it in from both sides there. But the big thing about Spain, of course, is not so much, the the fact that Orwell thought that he detected conditions of genuine equality in revolutionary Barcelona.

D.J. Taylor:The really big thing was what happened when he came back there, in mid 1937 after he'd been he was he recovered from being he's been recovering from being shot through the throat by a fascist sniper. Came back and, of course, of course found that the, the Republican hit squads sponsored by the the Soviet NKVD were on the march, and like unorthodoxy was being stifled, and, he barely got out of Spain with his life. When he got over the border to Perpignon, the first thing he saw was a list. His name was on a list in the newspaper, and, it was it was all under various friends of his, either, you know, were sort of banged up in Spanish prisons and sometimes didn't get out. So he was he was he was literally shot by both sides in Spain.

D.J. Taylor:And it was in Spain that he first saw, you know, totalitarian regimes in action and propaganda used used to the to the extent he was. So it was a very, very formative influence, I think, which we can manage all the way through to 1984.

Tim Benson:Yeah. I was just saying it was a good thing he's, you know, at least half a foot taller than the average Spaniard at the

D.J. Taylor:time. No. I would have been shocked for the hate if he'd been hard than the average Spaniard. Yes. Yes.

D.J. Taylor:Indeed.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Let's see. We're which time do we have left? About, 15 minutes. I guess I'm trying to figure out where well, I wanna make sure we get to Animal Farm and 1984.

Tim Benson:I mean, because I guess those are the 2 works people are most well, actually, just something about, just his other works that if people have not been familiar with them, that they all sort of they have this the the sort of the same general plot idea that runs through them, not in a dystopian way, but, you know, there's some

D.J. Taylor:Oh, you're absolutely right.

Tim Benson:Some solitary man who is

D.J. Taylor:It's solid all 0.1 point is the woman, Dorothy and Clergyman.

Tim Benson:So Yeah.

D.J. Taylor:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

D.J. Taylor:Yeah. You're right. They're all about rebellions that fail.

Tim Benson:Rebellions that fail. Right. Exactly.

D.J. Taylor:Yeah. This is much true about the thirties novels as the 2 and, of course, Animal Farm is about a rebellion that fails. Yes. And they're about, they're about, frightened, terrified, encircled solitaries on whom the world is ganging up. You make this minor attempted small attempted a rebellion, want to change their personal situation and it fails and they go back to the state they were in when they started, with 1 or 2 slight adjustments usually.

D.J. Taylor:And it's this. There it goes.

Tim Benson:Sorry, folks. We're having connection issues today.

D.J. Taylor:I'm with the It's okay. That's alright. So so, yeah, there is this kind of it is a kind of circular process. Yeah. And, I mean, in, in 1984, Winston Smith ends up being reeducated.

D.J. Taylor:There in some ways, the real the real tragic hero is Florie, the hero of Burmese Day. He's the very first 1.

Tim Benson:Connection issues again. Sorry out there, folks, everybody paying attention or listening that, we're having a little problem staying connected here. So, bear with us on that. Just gonna have to enjoy some dead air, I guess. Hopefully, we can edit this stuff out.

Tim Benson:Is it there? Yep. Hello again. Hello again. Don't know what happened there.

D.J. Taylor:You just it all just went blank.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Now you were We're

D.J. Taylor:talking about the the circularity of what happens to Oyle's heroes and his 1 heroine in his novel. We always somehow end up where they started again, with just some very minor readjustment. And it doesn't work, and they can't escape, and they and they've failed in their great endeavor. And, of course, failure was an or it was a light motif of Orwell's life. He he himself always thought he failed at everything despite his immense success.

D.J. Taylor:So, you know, you his own personality leaching out into this.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Well, success came for him rather I mean, obviously, he didn't live, very long, but success really didn't come for him until very late in his life. I mean, he had obviously, these, all these novels that he had published, but they didn't, you know

D.J. Taylor:Oh, no. You know? See, it's it's it's fascinating to to speculate what would have happened to his reputation had he died, say, of a bomb in the 2nd World War. Yeah. But we regarded him as a promising minor novelist and a very, very good essayist, but but nothing like the kind of you know, not nothing like the extraordinary reputation he has now in the 20 twenties.

Tim Benson:Sure.

D.J. Taylor:And so what I've actually I mean, what what I've tried to do in the in the new book, Who Was Big Brother, is, again, it accommodates a quite a lot of material. There just wasn't space for in a standard biography, if you see what I mean. So I'm very interested I'm very interested in what I would call Orwell puzzles, you know, particular psychological quirks, curious things about the major books that, have never really been satisfactorily explained. So, I mean, the who is big brother question is is an obvious 1. I mean, the smart 1 is on Stalin.

D.J. Taylor:But you see, you could argue that big brother doesn't actually exist, You know, that he's simply a sim Simple. Yeah. Created by the regime because they need somebody to worship.

Tim Benson:I've always I've always took it

D.J. Taylor:Oh, perfect.

Tim Benson:I've always from when I now, I've only read it twice in my life, and it's been a while since I've read it. And I I don't know why I haven't read it late. I guess because it's such it's so sort of depressing. And it's just like it's not I mean, it's a great book, but it's not, like, the funnest read. You know what I mean?

D.J. Taylor:Oh, 0,

Tim Benson:So it's just like, do I wanna sit through this again and, you know, have Winston Smith get, you know, honeytraps and, which I think he clearly that's the other thing too, the ambiguity with the, Julia character. IIII always thought even when I read it the first time that it was pretty clear that she that she honey trapped him for O'Brien.

D.J. Taylor:Oh, I think so.

Tim Benson:Because you

D.J. Taylor:see, when I when you look at if you look at the original manuscript, about about 30, 40% of it survives. It's a Brown University, the original. But there's a facsimile. If you look at the original manuscript, there's a very interesting canceled passage in it where, Winston coming back from O'Brien's flat when he still thinks O'Brien is is 1 on his side, bumps into Julia by chance and gets the impression of Will Wright that, that it was the last time that he would see her. And this doesn't appear at the final version because it gives too much away.

D.J. Taylor:You know? It suggests that the whole thing is a put up job.

Tim Benson:But, we're talking I mean, going back I

D.J. Taylor:mean, Animal Farm, for example, is much is funny despite having a tragic conclusion. It's funny. It's very amusing, and, which may or may not reflect the the influence of Eileen, Orwell's first wife. But you see, the big puzzle that 1 of the big puzzles in Animal Farm that interests me is what has Orwell got against the pigs?

Tim Benson:Yeah. He hates pigs.

D.J. Taylor:See, Orwell's the great, you know, fan of the the great admirer of the natural world. I mean, Orwell's Orwell was the great the great sort of, the the great sort of fervent, you know, praise singer of the British countryside and its and its form. And not

Tim Benson:the pig.

D.J. Taylor:But not the pigs. And this is, I found I hadn't ever thought of this before, but you see the anthropomization of the the the pigs looking like people and people looking like pigs actually happens years before, Animal Farm. So there's a passage in, Coming Up For Air written in 1939 where the hero goes back to the Oxfordshire town of his childhood. And he's walking up the hill and coming towards him, he sees what he thinks is a herd of pigs. And he's, what's going on here?

D.J. Taylor:How can this possibly be? You know? And what it is is a lot of children wearing gas masks Mhmm. Because they've just been

Tim Benson:Yep. More connection issues. Still there? Yep. Still here.

D.J. Taylor:So yes. So so there's this crowd of children all gas masked up, and for a moment, George Browning thinks that they're pigs. And so the he always said that he got the idea for Animal Farm in about 1937 by seeing a small child leading a horse, a big horse down a country lane and thinking, you know, what about if the horse didn't wanna play ball? What about if the horse reacted against all this?

Tim Benson:Right.

D.J. Taylor:But the idea of of human beings looking like pigs and vice versa, I think, came to him when he saw these children in gas masks just before World War 2. So it's things like that, I suppose, that I'm interested in. Puzzles about sort of little that quite often, you know, you can track them all the way back to little quirks in all else some psychology or little things that happened to him or sort of things from very, very early life that are then embedding themselves in his later novels. So that's what

Tim Benson:Like I said, I always I always thought it was pretty obvious, that Julia Honetrap.

D.J. Taylor:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:I mean, because she's

D.J. Taylor:me

Tim Benson:he's basically middle aged and, you know, not the handsomest of dudes and, you know, she's much younger. Know? And it's just like it's like the thing they tell all these businessmen when they go overseas and everything. They're like like, they have to I'm like, look, guys. If, like, if any attractive woman approaches you or, like, while you're overseas or whatever, like, it is 100% a honey trap.

Tim Benson:Like, there is no way like, it's just you might think, like, like, this might just be your lucky day or something like that.

D.J. Taylor:No. No. No. No. No.

D.J. Taylor:Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. So I thought it's the same thing with Winston.

D.J. Taylor:Julia obviously has a history. I mean, she has a prehistory of, you know, of sort of ruining members of the party. And in fact, the American writer Sandra, Newman has written a very good novel, Seeing, which came out last year, Seeing 1984 from Julia's side and sort of filling it back for it. Very, very good, I thought that. Because to me, Julia Julia is, is rather an absence to me in the in the in the original 1984, which means she has to exist, but you never really find out much of what's going on in her mind.

D.J. Taylor:And to me, the actual clinching passage is where they get hold of the famous banned book, you know, the principles of oligarchical collectivism. And Winston starts reading it too, and she falls asleep within about 5 minutes. And you think, that's not really the act of a revolutionary comrade, is it? So I I always had my suspicions from that moment onwards when I read that.

Tim Benson:Yeah. And, I just went oh, 1 thing I wanna bring up now that we're on 1984. You believe, and I think you're probably right, that 1984 wasn't that Orwell didn't truly finish it. That he had he lived longer, I mean, not major stylistic changes to it or anything, but he definitely would've, made some changes to the text before,

D.J. Taylor:you Yeah. The that's that's interesting. I mean, the you see, I've always always a very quick worker usually. Wrote a book in a year. He got the idea for 1984 at the as early as 1940 3, you know, when he

Tim Benson:Oh, wait. I know we're here. We're here. We're here.

D.J. Taylor:Yeah. So 1984 took him almost 5 years to write from conception to final execution. And some of

Tim Benson:that was to do with the fact

D.J. Taylor:that his health was declining.

Tim Benson:Sure.

D.J. Taylor:More of it was to do with the fact that he was still formulating, you know, the intellectual backdrop to it as he went along. And there are lots of essays written between about 1945 and 1947 that have some bearing on what finally happened. But I still think I mean, he I was saying earlier how he always thought he'd failed. Whenever he wrote a book, it was a failure. And he thought that he he said to a friend that he thought 1984 was a good idea that he'd mucked up.

D.J. Taylor:This is when he did. And, of course, by by the end of 1948, he was unable to do any more work on it. I mean, he was in a state of physical collapse. Yeah. I just have this feeling.

D.J. Taylor:It's got a kind of lurid hallucinogenic quality to it, which may well have had something to do with the TB that was ravaging his lungs. You know, there's probably some sort of physical connection here. And I just feel, I suppose, if he'd if he'd been able to contemplate it again, in conditions of mental and physical serenity, it would have been a slightly different book. And there's a kind of in in some ways to me, there's a sort of ragged quality to some of it, a kind of sort of sense that he's not quite got it to the extent that he would like to. And, I just think it would have been not not substantially, but I do think it would have been a slightly different book if he'd been in better health or it lived longer or Mhmm.

D.J. Taylor:You know, it it there's it's still got that kind of some of it's got that kind of provisional quality to me.

Tim Benson:Yeah. So 1 thing that obviously comes through in his dystopian works is his his fear of the technocrat. Oh, yes. Obviously, that's so what do you think Orwell would have thought, obviously, he had lived longer, of the, the the the the the second half of the twentyth century is really the rise.

D.J. Taylor:You say he was he was very influenced by the American management guru, James James Burnham. James Burnham is a key influence on Orwell. And he says several times that, you know, that Burnham is right, that the people who boss the world in the future will not be politicians You know, I mean, I don't I don't Orwell Orwell regarded technology as a as a means rather than I think 1984 technology is a means. It has to be there. You know, the whole the world the world of 1984 has to be existing in a tater techno fear.

D.J. Taylor:But I don't think Orwell actually very knew knew very much about technology or, you know, understood how it worked. And that's that's another 1 of the little puzzles that Yeah.

Tim Benson:That's definitely clear

D.J. Taylor:from both my book goes on about. And he he knew but he knew that that was what the future was gonna consist of. And so I think, you know, he'd had he still been with us, he would have regarded big tech with unutterable horror because it was it was faceless and unaccountable and oppressive and seductive and all these things. All these things, you know, that he that he, that he'd he'd sort of extrapolated from James Burnham back in the 19 forties, I think. You know, the future will be run by technocrats.

Tim Benson:Yeah. So, but 1 thing or I think it was in the the who is big brother book Mhmm. About the posthumous oral that a lot of people say you know, always argue about, you know, would Orwell would have had he got would he have gone more left at the age, or would he have, you know, gone, you know, more right? How would 1968 and the and the the the new left, how would that affected Orwell, blah blah blah, etcetera, etcetera. But really the most interesting question isn't that, but the or the most fascinating question as you write.

Tim Benson:The most fascinating question to be asked of the posthumous Orwell is what he would have written. So

D.J. Taylor:Oh, absolutely. You see, the thing is in terms of his reputation, I mean, it's it's always, it's always wonderful to speculate what what, you know, what he might have done had he lived. But in fact, his reputation depends on his death. Sure. Without Orwell dying, there is no Orwell, if you see what I mean.

D.J. Taylor:He had to die to cement the reputation.

Tim Benson:It was a pretty good career move,

D.J. Taylor:obviously. Career move to die. As to what he would have written, the only thing I can really point readers to, to your listeners to is so he writes Animal Farm 1984, these 2 dystopian classics, 1945, 1940. The only he before he died, he managed to scribble a few pages of what he thought was gonna be his next novel, And it's called a shooting a smoking room story. Mhmm.

D.J. Taylor:And it's set where on the boat back from Burma in 1927, featuring a young man, not unlike Orwell himself called, I think, Curley Johnson, who's been sent home from Burma in disgrace. So he's about 23, 24. And, it's stylistically very old fashioned. It reads like something by, say, Somerset Maugham or 1 of those, you know, quite sort of spay British writing, And it suggests that he was actually reverting to reverting to a much older literary form and a much different you know, going back to his roots basically.

Tim Benson:Reverting the type, basically.

D.J. Taylor:Reverting the type, I think I said. It sounds more like it sounds more like a coda to Burmese days than a a it's obviously not a dystopian novel. So I just wonder whether Orwell had he, you know, sort of carried on writing novels would in fact have, you know, would not have advanced very much further into the world of, of dystopia.

Tim Benson:Do you think maybe that I mean, how much of the success of the novel did he get to see before I mean, not much, before he died. I mean, the the financial He got to

D.J. Taylor:see enough of it. He got to see enough of it to be very sort of poignant about it. I mean, he he would sit there in his hospital bed with the first of the royalties pouring. He said, it's fairy gold, he said to a friend. It's just fairy gold, There's nothing But

Tim Benson:do you think do you think that if he had lived longer just to see the massive success of this, do you think he would have felt the pressure to, you know, give the people what they want and sort of write more in in that dystopian vein, or do you think that was a modeling I think

D.J. Taylor:he would have done exactly what he wanted to do. I don't think by that time that he was I mean, again, Anthony Powell, his friend Anthony Powell, made a very, very good, very, I think, pertinent comment about the the removal to Jura in 1946 after Animal Farm. He said as soon as Orwell had first taste, you know, the first fruits of success, he immediately retreated from it. Yeah. In other words, he didn't want to be a big star in literary London and go to parties and hobnob with TS Eliot or whoever.

D.J. Taylor:You know, as soon as he's successful, he goes off and sits on a Hebridean island.

Tim Benson:Well, part of that too was his fear of

D.J. Taylor:the the bomb. Bomb. Yes. Right.

Tim Benson:For his time, and he just figured, what? Let me get to a place that is most likely there.

D.J. Taylor:You know? I, you know, III can't ever imagine seeing him, but you complete pleased. But I think the idea of, Orwell would have hated being, you know, what we now call a public intellectual. He would have hated always being invited to sort of seminars Sure. And, you know, sitting on common that wasn't the way in which he operated.

D.J. Taylor:I mean, yeah, I think he he quite liked power, I think, but he liked it indirectly and it won't remove. Yeah. And would never have kind of sought a public role, I think.

Tim Benson:Speaking of that, like, do you, we talked about, you know, how he's the romantic streak in his personality. Do you think he also had sort of an I don't wanna say totalitarian or maybe like an authoritarian or or I

D.J. Taylor:know you know, I know exactly what where you're coming from here. I think it's it's he once said of the American writer Jack London, whom he greatly admired. He said that Jack London could foresee fascism, because he had a fascist streak in himself. And I think 1 of the reasons why Orwell is so good on authoritarianism is that he had an authoritarian streak in himself, which you can see. You know?

D.J. Taylor:There there was a kind of tough, no nonsense side to him as a very as well as a very gentle and and caring side. And I think he, you know, he he he he kind of knew he kind of knew what he was writing about when he came to came to 1984.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Alright. Well, I know you got a split, so, we just we'll just wrap it up here. Just 1 more question. The normal exit question,

D.J. Taylor:I It's been great fun, Tim. I've been

Tim Benson:doing it. Yeah. So the normal exit question we give everybody on this will, is that, you know, what, what would you like the audience to get out of this book or or these books, I should say? You know, what's the 1 thing you'd want you'd want the reader to take away from these 2 books having read them?

D.J. Taylor:I suppose I would like to, I suppose it'd be wrong if we'd say I want to make Orwell converts because, you know, most people do. Apart from a few old style of this, most people do regard them as well. I suppose I would like to I what I would like people to to leave, Reeves, with thought that there is much more to Orwell than, Animal Farm in 1984. Mhmm. If you regard his work as a giant bran tub, every dip in it will produce anything but bran.

D.J. Taylor:There is a prize gift there everywhere in the bin. You see what I mean? Even in some of the minor stuff, you know, book reviews written against time straight onto the typewriters, 19 thirties. It's all good. It all shapes up.

D.J. Taylor:Yeah. And that's something that can I I you know, there are most other major writers that cannot be said of them? You know? Homer in a lot of cases, Homer nods, and all else he has never nodded. It's all it's all prime prime quality material.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. I I love his essays. III think I might enjoy him more as an essayist than, and a critic than a novelist. I'm not sure.

D.J. Taylor:I don't know. I wouldn't I wouldn't put him in the front rank of novelist. I really wouldn't. I mean, I love his novels, but I think I'll I'll in a lot of work cases, I like them sort of personal reasons. Am I you know?

D.J. Taylor:And I'm I'm suspending a lot of critical judgment. The essay is superb. You know, the the the 1 of the greatest English essayists, I think.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Absolutely. I think that's a 100% true. Yeah. So but I I haven't I'm trying to think, though.

Tim Benson:I have not read Road to Wagon Pier, and, but I think that's the only 1. Mhmm. Mhmm.

D.J. Taylor:So I've

Tim Benson:read Down and Out. I've read Burmese Days. I've read Keep the Aspah District Flying. I've read Coming Up For Air. I've read Homage Catalonia.

Tim Benson:I'm trying to think off the top of my head. Is that everything other than Amber Berman?

D.J. Taylor:There are 9 there are the 9 published. There's 6 novels, 3 published works of nonfiction, and then Yeah. I think you've done pretty well there. Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. It yeah. But I'm weird. I read a lot. So,

D.J. Taylor:that's good for you.

Tim Benson:Not nor but, yeah. But I think that the essays I mean, I have the I think the Everyman's library has the the

D.J. Taylor:the Well, it's great. It's about the volume, isn't it? Yeah. Yeah.

Tim Benson:It's, like, 1400 pages or something, but I

D.J. Taylor:I have something with that. Start with No. No. 1 of those if you want to.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. Well, if you haven't read 1984 in Animal Farm, you know, obviously, probably start there. But, obviously, read this. And, also, read, if you need some more context behind the the works of of Orwell.

Tim Benson:You can read, mister Taylor's 2 new books, Who is Big Brother, a reader's guide to George Orwell and Orwell, the new life, the completely updated and reworked biography, from his previous, Orwell biography, which previous prize winning Orwell biography, I should say, which came out 20 years ago. Both, really, really, fascinating, fascinating works on a when you're writing about somebody who is interesting and fun in a way or idiosyncratic and just

D.J. Taylor:just a

Tim Benson:Orwell is Orwell is just his own dude. I mean, he's very, I mean He's

D.J. Taylor:not you're right. He's not like anybody else. Yes.

Tim Benson:Right. He's very unique.

D.J. Taylor:And I've the the great thing about writing about him all this time is that biographers, as you doubtless know, very often fall out of love with their subject.

Tim Benson:Oh, yeah. You can tell that why.

D.J. Taylor:5 years into the prod job. You suddenly I hate this book. I mean, I have never I have read, you know, I've read I've come across stuff that has caused me to qualify my judgments about certain aspects of his life and behavior. But I've never fallen out of love with him in 25 years. No.

D.J. Taylor:It's all I'm still burning with that gem like flame after all this time.

Tim Benson:Yeah. III just wanna say, 1 more question, I guess, because I just thought of it. As, you've obviously been writing for about him for so long. In the 20 years between these biographies, has anything have your opinions of him changed at all? I mean, obviously, you still like the guy.

Tim Benson:But anything else, have your opinions of him changed at all in the in the 20 years, between these 2 books? Is you know, or some aspects of his personality changed for you in any way?

D.J. Taylor:As as you know, there's there's been a there's been a feminist assault on Orwell in the last the last few years, and his behavior towards his first wife has been, which is debatable, but it has been exaggerated. And people have come, you know, they're great. Quite a lot of evidence has been suppressed, and certain other bits of evidence have been exaggerated. But I I think 1 of the things that struck me is, we were talking before about the people always being keen on answering the question, what would George have thought? And 20 years ago, people who were, you know, using him as this sort of savant and guide to the way in which the model world work tended to come at him from the the kind of what we call the hegemony aspects of 1984, you know, the contending land masses and, you know, parts of the world sort of ganging up against other parts of the world.

D.J. Taylor:And it's more recently, they tend to they they they begun to discover, the technological side and the manipulation of language side. When I was in Boston last year, I did an event at MITech with Steven Pinker, and I was Okay. It was very, very interesting because I got a completely different audience. You see, whereas in the UK, you get literary types and bookish people. Here I was at MITech with an audience full of, technicians and cosmologists and physicists and and and, and there is in all while.

D.J. Taylor:It was in AI, big or AI, big tech, manipulations of language, obfuscate. And and so, it was fascinating to me because I really had to start. I had to up my game rather than just answering the usual questions. I was being asked very different questions, which was very stimulating. And but that's that's, I think, where a lot of the interest in oil is coming from now, which wasn't so 20 years ago.

D.J. Taylor:So the I I can see different perspectives on it now, which is always a good thing for a writer's reputation.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Well, I mean, just in 20 years, we've seen the the rise of social media and That's right.

D.J. Taylor:To smartphone. And Orwell turns out to be relevant to.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Absolutely.

D.J. Taylor:To a lot of other things. You know? He's relevant to the whole eco environmental debate as well because there's a there's a buried subtext in 1984 about environmental degradation and, you know, deforestation and the and the the the spoiling of the the environment. There there there are all kinds of other perspectives there. It'd be interesting to see in 20 years time where we're where we're coming at, you know, from which angle we're we're coming in.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Absolutely. Alright. I won't keep you any longer. Like I said, I get around

D.J. Taylor:Thank you.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Thank you. So, again, everybody, Orwell, the new life, and who is big brother, a reader's guide to George Orwell. Check out both those books. I highly, highly recommend it.

Tim Benson:Really, really interesting.

D.J. Taylor:Thank you. It's been very nice at all.

Tim Benson:Yeah. No problem. And, so again, yeah, the my guest today, the author of those 2 books, mister David Taylor. So, mister Taylor, thank you so so much again for coming on the podcast and, you know, taking the time out of your schedule to do so. And, also, thank you for taking the time out of your life to, you know, write these books so that we can,

D.J. Taylor:Always happy to talk about Orwell. Yeah.

Tim Benson:Great. Cheers. Cheers. Alright. And, again, if you like this podcast, please consider leaving us a 5 star review and sharing with your friends.

Tim Benson:And if you have any books or have like to see us discuss on the podcast or have any questions or comments or anything like that, you can reach out to me at, tbenson@heartland.org. That's TBENS0N at heartland.org. And for more information about the Heartland Institute, you can just go to heartland.org, and we also have our, speaking of intrusive social media, we do also have our little Twitter, x whatever account, for the podcast. You can also reach out to us there if you have any questions, comments, anything like that. Our our Twitter handle, x handle, whatever, is at illbooks@illbooks.

Tim Benson:So make sure you check that out too, and that's pretty much it. So thanks for listening, everyone. We'll see you guys next time. Take care. Love you, Robbie.

Tim Benson:Love you, mom. Bye bye.

Creators and Guests