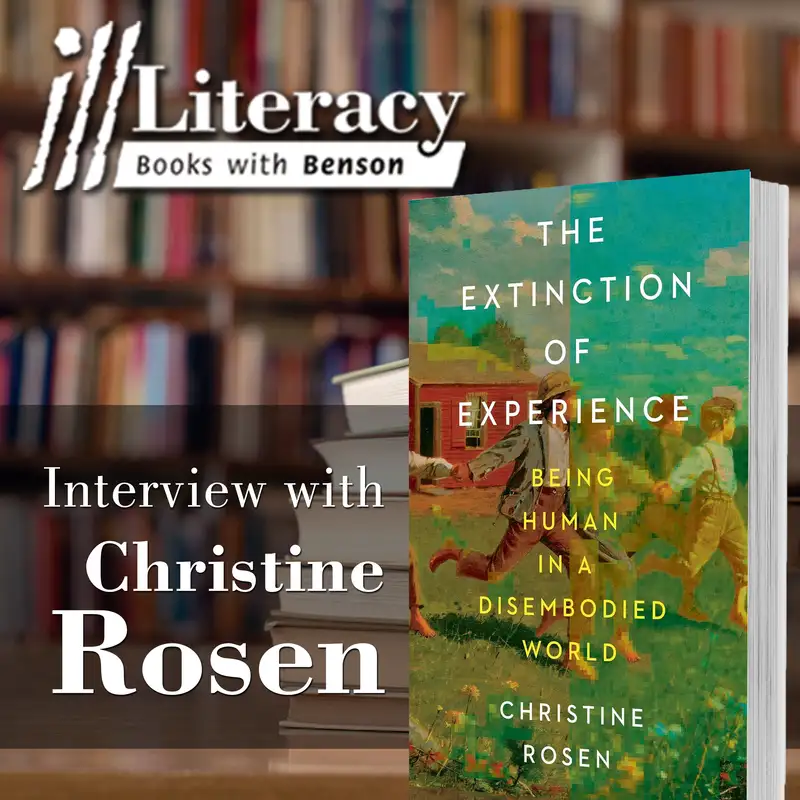

The Extinction of Experience (Guest: Christine Rosen)

Download MP3Hello everybody and welcome to the Illiteracy Podcast. I'm your host, Tim Benson, a senior policy analyst at Heartland Institute, a national free market think tank. We are in the episode a 170 something range. This might actually be episode a 170. But, anyway, somewhere around there.

Tim Benson:I can never remember the numbers. But, for those of you just tuning in for the first time, basically, what we do here on the podcast is I invite an author on to discuss a book of theirs that's been newly published or recently published on something or someone, some idea, some event, etcetera, etcetera, that we think you guys would like to hear a conversation about. And then hopefully at the end of the podcast, you go ahead and give the book of purchase and give it a read. So if you like this podcast, please consider giving Illiteracy a 5 star review at Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to the show and also by sharing with your friends, because that's the best way to support programming like this. And my guest today, very excited for this one, my guest today is doctor Christine Rosen.

Tim Benson:And doctor Rosen is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where she focuses on American history, society and culture, technology and culture, and feminism. She is also media commentary columnist at Commentary Magazine, one of my favorite magazines. Probably my favorite magazine if I had to come to my head, pick 1. And, she's one of the cohosts of the commentary magazine podcast. She's also a fellow at the University of Virginia's Institute For Advanced Studies in Culture and a senior editor in an advisory position at the New Atlantis, which is also one of my I don't know if you call it a magazine, but one of my favorite journals.

Tim Benson:Put it that way. Besides commentary in the New Atlantis, you may have seen her work in the New York Daily News, the Los Angeles Times, Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, the Washington Examiner, Washington Post, National Review, National Affairs, The New Republic, Politico, New England Journal of Medicine, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera, many, many, many places. And she's the author of many books, including Preaching Eugenics, Religious Leaders, and the American Eugenics Movement, The Why Success is Not Enough, and My Fundamentalist Education, A Memoir of a Divine Girlhood. And lastly, she's here to discuss her latest book, The Extinction of Experience, Being Human in a Disembodied World, which was published back in September by W. W.

Tim Benson:Norton. So that's a book we will be talking about today. So, doctor Rosen, thank you so so much for, coming on the podcast. I do appreciate it.

Christine Rosen:Thanks for having me. And please, I cannot prescribe medication, and I'm not the Yeah.

Speaker 4:Yeah. Yeah.

Christine Rosen:Yeah. The former first lady.

Speaker 4:So you can go back

Christine Rosen:to the team.

Tim Benson:Alright. Well, anyway, but it's just nice. I think you are actually this is really weird. I've had people on this podcast from South Africa, from Denmark, from Australia, Canada, elsewhere in Europe, all over the United States. I think you I'm pretty sure you are my first, fellow Floridian on the podcast.

Christine Rosen:Oh, I'm so happy. I'm honored. I am honored.

Tim Benson:Yeah. But did you are you you're from the West Coast, though. Right?

Christine Rosen:You Yes. I grew up in Saint Petersburg.

Tim Benson:I'm a little Yes. I live I actually live Saint Pete. That's one of my that's probably, like, out of all the downtowns in Florida.

Speaker 4:That's my

Tim Benson:favorite one. But, I'm on the Atlantic side. I'm about, like, 40 minutes north of, West Palm on Yes. Hutch Hutchison Island. I don't know if you're familiar.

Tim Benson:Yep. Yeah. That's funny. So, like, your side is, like, it's like Shelbyville to our Springfield or

Speaker 4:Exactly. Like, bizarre world

Christine Rosen:It's like a it's like an east east coast west coast rivalry we've got going on.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. I know. But it's it's it's it's weird. Like, every time I go over there, it's like Florida, but it's just like I just feel out out of place in it.

Tim Benson:Like, it feels like Florida, but it it's it's I still feel

Christine Rosen:like It's different.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Still feel like a foreigner in my my own state. But, anyway, yeah. So very lovely, you know, to have a floor rating on the podcast. Finally.

Tim Benson:Finally broke that curse. But, anyway, getting to the, the the book itself. Well, I guess, the normal entry question to everybody that comes on the podcast, and that is, you know, what, what made you wanna write this book? What was what was the genesis of of it? What was the genesis of the project?

Christine Rosen:Well, I have been, thinking about writing about technology for a very long time now, since a small group of friends and I started the new Atlantis more than 20 years ago, and, I've been especially fascinated with how it changes human behavior. But for me, the real impetus was raising my kids and seeing the very different world that they were growing up in and really wanting to check my own priors and not become the full fledged Luddite I'm probably prone to becoming and always to question, okay. So if they're not teaching them cursive handwriting, is that the end of the world? Let me look. Let me research.

Christine Rosen:Let me see what I can find out. So there were there were dozens of those sorts of moments throughout their childhood that I just started keeping a folder in a notebook and jotting things down and noticing things. I'm I'm a gen xer, the best generation. And we, I was noticing things that were just disappearing from life that I used to take for granted, and it all kinda came together. I was reading this essay by this naturalist, Robert Michael Pyle, and he was talking about kids not going out in the real world and mucking around and getting to know what it's like in nature, and he called this experience he worried about the extinction of experience by which he meant they wouldn't be raised in a world where they understood what it meant if a species went extinct or something disappeared and that really stayed with me.

Christine Rosen:Years after I read that, essay, I was I was thinking about how technology was doing that with some of our human interactions. So that was the sort of genesis of it, but it's really been basically, you know, 15, 20 years of just observing the changes in our own human interactions that, that are the result of the embrace of these really wonderful tools that we all use every day, but trying to think through some of the things that we've lost as well as gained.

Tim Benson:Mhmm. Yeah. I'm with you. I, I'm not I'm I'm not gen x, but I was so

Christine Rosen:so sorry. So I

Tim Benson:was born in 1982.

Christine Rosen:For the worst.

Tim Benson:No. No. So, like, I was born in 1982, so I'm not really, like, a millennial either. Right.

Christine Rosen:Like, no. There is that generation that kinda doesn't quite fit.

Tim Benson:And and Yeah. And I'm, like, way more, like, culturally, like, comfortable with Gen X and, you know, just the things that I watched when I was, you know, on TV.

Speaker 4:Mhmm. As a

Tim Benson:kid, we're just, you know, much more you know, the music I listened to and all that stuff. But I you know, it was something I became you know, obviously, when you have kids, you look at everything different. But I remember, you know, the first time I really thought that, like, oh, shit. We might be in trouble here is I was on a flight. This is when I was still living.

Tim Benson:I was still working at the Heartland headquarters in Chicago, and I was flying from Chicago to DC for some work thing. I can't remember what it was. But, so I'm in O'Hare sitting at the gate, and I'm one of those people that I always bring a book on a flight. I never always have a book with me no matter what. And so I'm sitting at the gate, I get at the gate, and there's 60 kids sitting at the gate.

Tim Benson:You know, like 8th graders, they do, like, their that class trip to DC, and, like, also, it was like the whole 8th grade class, whatever school this was that were on the flight. And so all these kids are just sitting in the gate area. And every single one of these kids had the phone in front of their face and was just on the phone, and and just, like, staring at the phone, but, like, while having conversation with, like, the people seated, like, next to them, but never taking their eyes off of the phone and just, like, having these f, ephemeral conversations with whoever, and they were just all staring at it. And then, there was another time when a group of friends of mine or me and 2 buddies went to see the national championship game, football game in New Orleans when it was the year that Alabama played LSU. So my buddies from Thibodaux, Louisiana, he's a big LSU fan.

Tim Benson:And his little sister at the time was at University of West Florida in Pensacola. So stopped on the way, picked her up, picked up one of her friends. She got to turn 21 in New Orleans.

Christine Rosen:Great place to great place to do that.

Tim Benson:Which in retrospect wasn't the best idea. But She

Christine Rosen:had chaperones. That's great.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. So anyway but so so we were all stuck in, like, this one room because it was, like, $500 a night, and, you know, we just happened to, like, lock in. There's, like, one king-size bed.

Tim Benson:So us 3 dudes, like, slept on the floor, and the girls, you know, took the bed. So, anyway, like, they would wake up in the morning, the 2 of them, and the first thing they would do when they woke up immediately, phone. Phone. Social media. Social media.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Just and I was just like, Jesus Christ. These kids are just like

Christine Rosen:They are not like us.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Like, they're just immediately that's the like, what they and then it's like, we might be like, I don't I was like and this was 10 years ago, and I was like, we might not really comprehend how much this is gonna change in a society, you know, very quickly.

Speaker 4:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:And, it was just sort of an eye opening experience for me just watching, like, kids in their element.

Christine Rosen:Well, and those kids at the time were being told that this was good for them. This was great. Look at how they're connecting. They're talking to all their friends. They're in touch.

Christine Rosen:And it really was a massive social experiment on an entire generation of American children.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. And now those, I mean, this was probably 10 years ago. Now those kids are probably in college at this point or more. And like my friend's sister's in her thirties now.

Tim Benson:So, I feel very fortunate that I was old enough to, like, have the Internet when I was I mean, we you know, I was around, like, 11 or 12 when, like, everybody got AOL and, you know, dial up speed

Christine Rosen:Oh, that dial up mode.

Tim Benson:And the guy just died that you got mail guy. Yeah.

Christine Rosen:The voice. Yep.

Tim Benson:But it wasn't, like, ubiquitous. And even when I was in college, Facebook wasn't really like, I don't you know, I I think maybe, like, my senior year of college, like, Facebook became a thing where, like, everybody got Facebook, and but it was still, at the time, like, only certain universities had it, so you had to, like, sign up with your university email. And, like, all the normies didn't have Facebook yet, and it was all exclusive and stuff. But so, like, my entire, like, childhood, young adulthood was sort of free of that entire ecosystem that now exists. I didn't have a digital avatar, a representative, for my and I never had to think about it or spend any sort of mental juice on crafting that persona.

Tim Benson:And, so I just I feel really, really blessed that I came along just at the just at the end before everything is probably gonna go to crap. But

Christine Rosen:Well and you you also what you got what I got any of us who had what you can now basically call an analog pre smartphone childhood, we I think we now appreciate something, that we got because now you can't take it for granted. There you have to choose this now, which is to learn those unspoken written rules, to to learn how to look someone in the eye when you have a conversation,

Speaker 4:to

Christine Rosen:learn how to be bored, to learn how to make your own fun and and actually get out of the house and and and have parents who generally, either because they were they couldn't be bothered or they trusted you more, let you go out into a world and experience some moderate amount of risk. So I do think that we those are all things now that social scientists are earnestly studying and telling parents, oh, you have to choose this now. We got to we should be grateful that we that there was no option because it turns out a lot of those experiences, including the many tetanus shots I got when I with my friends would find a, you know, an abandoned construction site. They did teach us certain skills that have translated into adulthood that that have helped these are human skills, things we can no longer take for granted if you're being raised in a world where everyone's staring at a phone.

Tim Benson:Yeah. And it's just, you know, I don't know whether my parents were just, like, nuts or I mean, there's just, like, certain things. So I, you know, I live in Florida now. I've been down here for 25 years almost, but I grew up in New Jersey on the Bradley Beach, on the shore in Monmouth County. But my parents, when I was like 11 or 12, around there, they would just let me take the train into the city, just go, you know, bum around, and there was no cell phones.

Tim Benson:I would just be on another toggle case.

Christine Rosen:A phone. You could there's a

Tim Benson:phone or other Right. But, I mean, like, they couldn't, like they had no idea where or something.

Speaker 4:Yes.

Tim Benson:Yes. And, I think about that, and I was like, would I let my kid do that today? And, like, the city is, you know I mean, granted it's not as safe as it was 4 or 5 years ago, but it's probably safer now in terms of, or at least murder and those sort of things Mhmm. Than it was in 1992 or 93.

Christine Rosen:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:And, like, would I let my son, like, just go off, you know, on a probably not. I don't know. And I hate that, but but, like, I

Christine Rosen:Well, but but you should but those are so those are the kinds of habits of mind that our technologies have cultivated in this, which is if you can survey and track, that should allow you to give to grant more freedom to kids. Right? Oh, well, they have a cell phone if there's an emergency. But in fact, I think it's cultivated, social expectations and habits of mind that make us more fearful and and and less enable unable to kind of calculate real risk versus you know? No.

Christine Rosen:I agree. Like, I used to leave the house, and it was like, come home. When the when the street lights come on, you gotta be home. That was Yeah.

Tim Benson:But it feels different. I don't know if it's just like well, part of it, I think there's, like, there's just not as many kids around. I don't know. It's just because the declining birth rates because, you know, like, when I was growing up, there was just, like, kids everywhere. You know?

Tim Benson:Like, all the families were, you know, about, like, the same age. You know, they had kids in, like, you know, probably, like, an age range of, you know, like, between, like, 14 and, like, 6 or something.

Speaker 4:You know

Tim Benson:what I mean? Like, there

Christine Rosen:were There were older kids who would watch the

Tim Benson:younger ones.

Speaker 4:Yes.

Christine Rosen:Yes.

Tim Benson:And it's like where I live in Florida, I mean, like, granted, you know, it's there's not as many kids around. I mean, it's mostly just not entirely, but mostly, like, retirees and, like,

Speaker 4:full people.

Tim Benson:And, so, you know, I I would feel more comfortable, like, letting my kid I mean, he's only 4. So, I haven't really got to, like, that point yet, but, like, I feel more comfortable

Christine Rosen:in the tyrant phase.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. Right. Yeah. You just you should've seen him this morning before school.

Tim Benson:I would feel more comfortable letting him out and just being, you know, and with unsupervised if there were just more kids around, but

Speaker 4:there's just

Tim Benson:not as many.

Speaker 4:And then

Tim Benson:I don't know if that's just something that's more Florida specific. Like, maybe it's not true elsewhere. I mean, it just might just be the demographic. Then there's a lot more young people that live here now than, like, when my dad retired and we moved down here in the very late nineties. It has definitely changed in that regard.

Tim Benson:But

Christine Rosen:There are fewer children outside of their homes these days in general. And then and if you look at the amount of time that they're spending on screens look, for the average adult, it's about 7 hours a day. It's much, much higher for younger kids. That's the opportunity cost. They're not outside playing in the neighborhoods.

Christine Rosen:They're not actually meeting up face to face and they are, as they get older, particularly in their teenage years, they're expressing a very strong preference not to do that, to not be in person with their friends. And as a result, they spend a lot more time alone. They spend a lot more time, they have fewer friends than I think a lot of us did growing up. And and so it's not a surprise they also have higher rates of anxiety, depression, loneliness. I mean, these are these these are these are kind of all related.

Christine Rosen:They're not entirely, it's not entirely correlation causation, but it but but there there are some real trends that start you can see them starting in the early Internet era and just really kind of gaining steam.

Tim Benson:Right. Yeah. And it just seems like everything is way more structured. Like, there's, like, play dates and stuff. I mean, like, I mean, but, I mean, you know, when I was a kid, you know, there would just be the kids in neighborhood, and there would be, like, you know, the 1 or 2 kids in neighborhood, like, you actually, like, really didn't like.

Tim Benson:Right. But, like, if you wanted to have a pickup baseball game or something like that, you know, you wanna go play Sam at Ball or something like, well, you gotta bring him along. Figure

Christine Rosen:it out.

Tim Benson:You have to bring him along because you need you know? And then you guys have to figure out how to, like, you know, work with each other and

Speaker 4:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:All that stuff. And that seems to just be I don't know. I mean, I don't know if it's completely disappeared, but it seems to be like it's something that has been just in rapid decline since, you know, 30 I mean, oh god, 30 years ago.

Christine Rosen:Well, there are I mean, those but those social skills, it's funny. Everyone always, tends to be like, oh, well, that's things change. It's fine. But I I think you're onto something here, and I think it's important because people should recognize that a deterioration of those skills really does have a long term effect on our culture and our society. We certainly know it's had an effect on our politics.

Christine Rosen:But that kind of very low level negotiation and low level tolerance of annoying people,

Speaker 4:you

Christine Rosen:can actually opt out of that at a very young age in this in this culture if you have a smartphone. You can just stick with your friends, you can be on social media, you can just not be involved with people who disagree with you, and you can spend your time in this in this very, perfectly curated world. And that actually means when you become an adult and someone in your college class or at your first job turns to you and says, well, I think that's crazy. I like this guy for president. Your head explodes because you've never confronted a view that doesn't conform to your own.

Tim Benson:Right. Or if, like, or if you're an asshole, sorry for Chris. You know, like, you don't like, back then, if you were an asshole, like, you got punched in the face.

Christine Rosen:You were rewarded for it. Right?

Tim Benson:Right. Right. Right. Like, now,

Speaker 4:like become an influencer.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Exactly. Now it's just like you hide behind your phone, and you're just an asshole all day long to everybody. And, like, you haven't got punched in the face enough to realize, like, that's not how you you know? Right.

Tim Benson:Anyway yeah. So,

Speaker 4:I think

Tim Benson:we're onto something. More punches to the face.

Christine Rosen:Here we go.

Tim Benson:Alright. So I I alright. So I guess a big picture question, because you talk a lot about humanism in the book and how we need, a new version of it. So just, I guess, for the people out there who might not, you know, really understand what human humanism is, what is humanism, and why do you think we need a new, version of it?

Christine Rosen:So what I meant by that, and I borrowed heavily from Richard Sennett and others who've who've described a way of being in the world that is human centered. And by that, I mean, the the kinds of, first order questions, whether they're about justice, equality, connection, home, community, Those should always begin with human values. And we might shrug and say, well, that's what we do now. I I don't think we do. I think we actually often s elevate, you know, algorithmic and machine like values.

Christine Rosen:We we don't even use the word virtue anymore very often. That word makes you sound like a fusty Victorian.

Speaker 4:Mhmm.

Christine Rosen:But these are the sorts of things that ground us in what it means to be a person. It it teaches us from a very young age about risk and contingency and human nature. And I think what we've what we've created is a world that's very, as Mark Zuckerberg promised us, frictionless, seamless, easy, efficient, on demand, all of these things. And we think, wow. We're amazing.

Christine Rosen:Look what humans have created. But we forget the other part of that, which is that as we use these tools more and more often, as we allow them into our homes, onto our physical bodies, allow them to to take over vast swaths of our culture, we start to conform to the demands of the machine. So what a what a humanist perspective says, and this will become more and more crucial as we as we move into the era of artificial intelligence, is to say humans first. And now we're in a world where we have to actively choose the human. For example, you have to actively choose to be face to face with people because it's much easier not to be, including the people who you most care about and most love.

Christine Rosen:And so mediating that is the default when I would argue being in each other's presence, which is harder and more annoying and makes you have to leave the house, all these things. It's still better. And sometimes we have to choose the the less appealing alternative, which which is mediating that, but that should not be our first order of business. So when I think about human humanism, I think how do we make the world and particularly the private sphere, more human centered because we have, without really thinking about it, allowed these technologies into our private lives, into our homes, into our real personal relationships in a way that has really degraded them, and we're just starting to wake up to that fact but I think to go moving forward, we're not gonna get rid of our phones and the internet and we shouldn't but we have to be much more thoughtful and aware of what it's doing to us even as it's giving us things that we love to do.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Right. I mean, that's, you know, I'm not on any sort I mean, I have a Twitter that I, like, lurk on and I use for, like, news and information, that sort of stuff, but, like, I never post. Mhmm. I never had an Instagram.

Tim Benson:I mean, I had Facebook and MySpace, you know, back in the day. But

Christine Rosen:Oh, MySpace. Oh, you're old school, man.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. BU. What did someone call it?

Tim Benson:Like, the the abandoned amusement park

Speaker 4:or something

Christine Rosen:like that. Right. It's, like, falling apart. It's horrifying.

Tim Benson:Yeah. No. But I but it was never, like again, like, I was just old enough that it wasn't really, like, central. And I remember, you know, when, like, everybody got Facebook, and then it was great at first because it's like, oh, it was all these people that, you know, I haven't talked to since high school or whatever or grade school, and you you you meet and stuff or you follow each other and keep up. But but, like, I noticed that it was, like, changing me, you know, you know, in a way and, you know, what I chose to post and, you know, comment on and like and all that stuff.

Tim Benson:And I just remember, like, I I don't know what the turning point was, but it was just like it it just felt air stats. You know? And, and I just kinda sorta got fed up with it. I remember there was, like, like, one girl I went to high school with was her kid had, like, chicken pox, and she took all these photos of, like, the pox all over his kid, like, in his ear and, like, all this and, like, posted it to, like, Facebook. And I was just like

Christine Rosen:That poor kid.

Tim Benson:Yeah. I know. It's like I was like, no one needs to see this. What the hell are you doing? Like, why do you think we wanna see your kids?

Tim Benson:Anyway, and then, like, you know, things that happen in, like, my friends' lives, like like, like, a a dirty secret that I knew about that, other people didn't know about about a friend of mine. And, anyway, I I won't get into it, but but just seeing, like, him and his wife, you know, just, like, post, like, normal, like, happy shit all the time. And it's just like it's just like this is all totally yeah. Like, this is

Speaker 4:They are conforming rationally to the demands of the platform, and that's why

Christine Rosen:you I think you're, again, you're expressing, And that's why you I think you're again, you're expressing a

Speaker 4:very important intuition that I think a lot of us dismiss because we think, oh, this

Christine Rosen:is the future we have to adapt and adapt and blah blah blah. But the truth is that intuition is something we should listen to. What you're what you were feeling was an unease, a discomfort with seeing people perform their lives when you actually know them as people. Right? Know them in their real world, their full human context.

Christine Rosen:So you know their beauty, but also their ugly side. And that's how we're meant to know our closest friends and fam. We're supposed to know each other that way because it builds bonds of trust. And that is, I think, again, if you imagine if most of your friendships were formed through that filtering prism where everybody's sort of performing rather than being themselves or being a version of themselves that isn't truthful to who they are. Yeah.

Christine Rosen:It becomes disorienting.

Tim Benson:Right. And then it was just, like, when I finally decided to you know, when I was weighing my mind whether or not to get rid of it or not, and I was like, well, there's all these people that,

Speaker 4:you know, I

Tim Benson:won't be able you know, at once, you know, we're, you know, we communicate on here and stuff. And then I was like, well, if I don't talk to them in my real life anyway, like Right. What who who gives a shit? Like, I mean, I mean, we're not really friends. You know?

Tim Benson:I mean, like, we're

Speaker 4:This is the

Christine Rosen:yeah. So this is the other thing that drives me nuts because I've never been on social media. And I had a lot of my my siblings are on social media, and they I they would send me these angry messages from people I'd gone to high school with. So why isn't she on Facebook? We're all on Facebook organizing this and that.

Christine Rosen:And I said 2 things. The first thing was I didn't wanna stay in touch with some of those

Tim Benson:people from high

Christine Rosen:school. They weren't nice. Right. The ones I did, I found ways to stay in touch with, and I'm still in touch with some of them. But there was a way in which there are these natural stages of life that we are supposed to grow and move on from.

Christine Rosen:One of those is childhood. To become an adult means to leave childish things behind. And some of those childish things did rest in very deep and meaningful friendships at the time when we were 13, 14, 15, 16. But moving past that is completely normal. That's a human stage of development.

Christine Rosen:And I feel like these these tools have done 2 things. 1, they've robbed children these days of having that open past unburdened, not to sound like our recently failed presidential candidate, but unburdened by Amazing how that word is just gonna be associated with their privacy. Completely tainted. It will never not be said ironically going forward, nor should it. But but this idea that you can't have an open future because every stupid thing you did from the age of 11 on, and maybe earlier if you're that poor kid whose mom is trying to become a momfluencer and putting your chicken cox stars online Yeah.

Christine Rosen:You you don't have a past that can be shaped in your own mind and going forward, the kind of adult you wanna be. It it it blocks off change, and

Tim Benson:I think that's that. You hear all these stories of these kids. They're, like, the 1st generation of the kids whose, like, parents were, like, totally into social media and posted all these pictures and all these things of their childhood. And these kids are finding out about it. And they're like, what the hell?

Tim Benson:Like, I never can send it for you to send this on to to the entire world

Christine Rosen:Yeah.

Tim Benson:And all that, and, you know, the sort of the the blowback from that. Mhmm. But I yeah. It was just, like, the way it changes people. The other thing, like, I noticed you might not have noticed this because you were never on social media, but, like, there, like, there was, like, an arms race, like, when Facebook first started with, like, maternity photoshoots and, like, the, like, the pregnancy pictures where, like, 1 girl went out into the field and did the thing where they hold the belly.

Tim Benson:The husband holds the belly and all that, and they take all the shots and all that. And then it was like so some girl did that, and then her girlfriend was like, Okay, well, we gotta do that, and we gotta do that better,

Speaker 4:and

Tim Benson:more expensive. And then it was just like I just kept seeing Everyone had the couple maternity photos or something like that. You know? That, like, they went to, like, a portrait studio or did, you know, back in the day. But now it's like and then, like, everybody's, like, wife became, like, an amateur photographer, like, you know, company.

Tim Benson:You know what I mean? But then

Christine Rosen:it gets but it's hamat. Right? So this special experience becomes a homogenized thing.

Speaker 4:Right.

Christine Rosen:Yeah. Everybody does. It loses its distinctiveness.

Speaker 4:I I had 20 And you can't not

Christine Rosen:I didn't have any photos taken. I'm like, I look like a parade float. Keep your

Tim Benson:curtains away. But then, like but you can't do it because if right. Because if you don't do it, then it's like, oh, well, you know, what's up with them? How come they didn't? Right.

Christine Rosen:Is she ashamed of her prague beautiful pregnant body?

Tim Benson:Right. Right. How come she didn't have the sign and, like, the truck on top of the belly and, like, all that stuff.

Christine Rosen:Like the gender reveal stuff too.

Tim Benson:Oh, god. Yes. That's another one.

Christine Rosen:This is all so if you notice so when when I was growing up, this has happened with gender reveal, happened with all the stages of pregnancy now, and it's even with prom, asking someone to the prom. And I will say my kids are 18. They're Gen z. They grew up, but but they have this healthy skepticism and cynicism about social media because they saw that the generation just before them doing this. So for all of their prom, I mean, they went to public school, so I think it was maybe a little different at the private schools in town.

Christine Rosen:But they are like, yeah. I'm just gonna ask her to prom. I was like, excellent. So there is a there there's hope for a future where everyone's performing a prom proposal.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. Right. No. I think, that all started with that MTV show.

Tim Benson:What was that? Yes. Beach or something?

Speaker 4:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Tim Benson:That's that's the one that

Christine Rosen:The promposal. But but it spreads. Right? That's what social

Tim Benson:media designed. Every dude in the country that was every dude when that came out,

Speaker 4:every every I avoid.

Tim Benson:Was just like, oh, no. Like, I have to put this much plan in.

Speaker 4:Thing that women expected. Right. Exactly.

Tim Benson:Yeah. That was the, anyway alright. So, one thing I really found interesting about the book just because I have another personal, tie in to this, is your visit to, the Abbey of Our Lady at Gethsemane, which is the, Trappist monastery in Kentucky. And, my great uncle actually was, a Trappist. He was at oh, he was at Gethsemane for a time, but he was at the Abbey of Our Lady, the only trinity in Huntsville, Utah Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah, yeah, which doesn't exist anymore. They've well, basically, all the monks died out, and the older ones, they just They moved over to other

Speaker 4:places. Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Nursing homes and stuff. But the land there, actually, thank God for the Mormons at Utah. They're trying to conserve the land where the monastery stood, and keep that land open space. The monks are buried there on the property, so they're gonna keep that.

Tim Benson:They're probably not gonna keep the buildings, which are just like you know, old quonset huts and

Christine Rosen:Right.

Tim Benson:Whatever. But, for for those people that aren't really familiar, the Trappists are basically like this really hardcore version of the Benedictines, and

Speaker 4:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:They observe the strict observance of the rule of Saint Benedict, which, basically, it's you speak pretty much only when it's necessary to speak, and that's about it. Right.

Christine Rosen:And most

Tim Benson:of the day is in silence, and their day is basically broken up into 3 parts, 8 hours of rest, 8 hours of work, and 8 hours of prayer.

Speaker 4:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:And it's a contemplative life, and you know, it's very quiet and peaceful. And I got to I was fortunate enough to go out there a few times before, my uncle passed away, and the moms just started getting too old. But, yeah. So why don't you tell everybody about your visit to, to guest. I mean, oh, my uncle.

Tim Benson:Actually, my grand another thing. My great uncle was, he was basically, like, Thomas Merton's typist. Like

Christine Rosen:Was he? Oh, wow.

Tim Benson:He was he, like, dictated or Merton, like, dictated, and he typed in

Christine Rosen:that name. Everyone should read Merton. I I mean, regardless of your religious, proclivities or affiliations, he is just he's especially, he was especially prescient about modern anxieties, I would say. He's writing in a previous century, and and so much of what he says really still has has held up. So I I went, total cliche, writer's like, I'm gonna go to a monastery and understand this totally different world.

Christine Rosen:It was ridiculous. But I, they were perfectly lovely. They do allow for people to come and stay. You stay for a week and you you can choose to do it's a choose your own adventure. They don't force you to do anything.

Christine Rosen:They're basically just like, leave us alone to do our thing and here's the schedule. So but I kept the schedule. I was getting up in the middle of the night and going to each prayer and do I I wanted to see what it was like to live that way. And, I thought I would write about time, how they understand time in a very different fashion, in a slow long term fashion, but I was struck. They are the most patient human beings on earth, and they are all about waiting.

Christine Rosen:And so it became I I was able to talk to a few of them, and and then I, you know, read everything, Thomas Merton. I'd read some of what he'd written before, and I kind of really delved into, sort of the Trappist lifestyle. And it was such a lesson for for modern sense of a modern sensibility like mine about not just waiting as something you endure, but waiting as this joyful experience because they are waiting to hear the voice of God. They and they will wait their whole lives and are perfectly satisfied knowing they might never hear it. And that just struck me in a in a world, in a culture where it's like, you must go for what you wanna get it and cannot impatience is not a virtue.

Christine Rosen:It just it was so striking to me. I had my kids were much younger at the time. And to just be away and in that quiet for a week was was it like a people are like, I'm going to the Canyon Ranch. I'm like, oh, I got a better place for you. Like, nobody talks to you.

Christine Rosen:You just you just be.

Tim Benson:No. I mean, like, I remember, I think, like, the I don't know. I was out there when I was 8 and, with my grandparents. So my the my grandmother, his her brother was the, Trappist. And, so, so my grandfather and I and father Alan, which is one of the other monks, I guess we decided we were gonna go climb Mount Ogden, which, I don't know, was probably, like, 8, 9000 feet, something like that.

Tim Benson:And, so it took I mean, that was, like, 8, and I was like, oh, 9,000 feet? That's not that far. That's less than 2 miles. Fucking brutal. But I did it.

Tim Benson:My grandfather didn't make it because of his knees, but so it was just me and father Alan, and we got to the top, and and he was just like, now I just want you to just sit here and just look and observe and just don't say anything. And I was like, alright. And so we sat. I don't know how long it,

Christine Rosen:Ah, time stills

Speaker 4:when you sit and look. Yes.

Tim Benson:And so and I was like and I know there are rules about, you know, silence or whatever. And I'm sitting there. I'm like, alright. How long are we gonna sit up here? And, I I really don't know how much time is spent, but, you know, I appreciate what he was trying to do for me.

Tim Benson:And, you know, it's still something that, like, I you know, childhood the older you get, more and more of childhood becomes hazy, you know, with your Mhmm. Recollections. But, there's still a lot of that that I really, vividly recall. You know? Mhmm.

Christine Rosen:So Well, that the sitting still and just waiting Mhmm. Is is For a

Tim Benson:kid, it's For a

Christine Rosen:kid, it's always been difficult, but it's now a completely alien experience for a lot of adults too. I mean, I I talked to a bunch of, you know, art history professors and other people who deal with visual culture, entertainers. And one of their biggest complaints about the people who come to see their work is that no one can just sit and be and think about what we've done. Like, painters are like, you you go through a museum now. You go through an exhibit, and people just run by each painting.

Christine Rosen:They might take a photo of it. Off they go. There's no patience for really trying to submit to someone else's vision of the world. And then what the monks, I think, do is submit to God's vision for them and they do it willingly and it is their entire life. But for every person, we need to carve out moments like that in our own lives even if we're in a secular context where we say, you know what?

Christine Rosen:I'm gonna set aside this my day to day life and I'm gonna just contemplate whether it's a film or music or I mean, I actually some of the best moments I've had that are analog lately have been comedians like stand up where they force everyone to put their phones away.

Speaker 4:Yeah.

Tim Benson:And you

Christine Rosen:have this really great experience where of camaraderie with all the strangers in this small bar that everyone's listening to a usually bad stand up, you know, except for a performance. But it's great.

Speaker 4:It's so

Tim Benson:much fun. No. Yeah. Like, you made the point in the book, you know, going back to museums and just, you know, people and you got their selfie sticks, and they, you know, take the picture with the Mona Lisa and all that. But the mediation of art, fosters an impatience for, you know, what art demands.

Christine Rosen:Exactly.

Speaker 4:Yeah.

Tim Benson:And, yeah. And just the thing with the comedians at, night and day difference, I actually just went and saw, Taylor Swift, a couple weeks ago when she was in Miami. Long story how that happened.

Christine Rosen:I don't see your friendship bracelet, so I don't believe you.

Tim Benson:No. No. I went. No. I'm actually somewhat of a fairly decent Swifty.

Christine Rosen:Okay.

Tim Benson:But, yeah. So, anyway, long story. But so me and a, some friends. And, but I was just struck by how much time of these and, like, the Swift I mean, that's not really, like, my, like, kinda concert thing. You know what I mean?

Tim Benson:Like, I like Taylor Swift, and I went I don't think I'd probably go see it again because it's more just like a like a performance, like Cirque du Soleil or something like that. It's not like acting live music. But, it was very communal, but, like, all these I mean, it's amazing how much time people spent or these girls spent for the most part. That was one of the nice things about it being like a guy at the, like, the bathrooms. Yeah.

Tim Benson:Like, it's the first time in my life I've ever been to, like, a stadium where, like Yeah.

Christine Rosen:Dude, there's no life.

Speaker 4:Urinal and

Tim Benson:yeah. Anyway, so, like, I had the whole bathroom to myself. I was like, this is amazing. But just how many of them just, like, watched the concert through their phone? Yeah.

Tim Benson:You know? Just taking videos. They document the experience. Turn the phones around Yeah. You know, and all that.

Speaker 4:And I

Tim Benson:was just like, you're not actually watching it. You know? Like, I mean, you'll have all these documents that you you know, all these pictures and photos that show you were there and then but you didn't really experience it because it's all through the phone. And it, like, drives me nuts when I see this in, like, sports, you know, when, baseball when, like, you know, they're all these people just standing up, you know, on the phone, waiting for a strikeout or, you know, something to happen. It's like, just watch the freaking game.

Tim Benson:Like, you know,

Christine Rosen:it's like They this this fascinating to me because this has been happening since cell phones with cameras first appeared on the scene, and I was always scolding people for it. And they're like, oh, you're just you're just being a crank. But there's real research behind this now. There have been these extensive studies of what we retain in our memory of an experience if we film it versus if we just pay attention, and you will remember less. And, you know, you're you were speaking earlier about this sort of very memorable experience as a kid.

Christine Rosen:Had you sat at the top of that mountain and filmed it, your memory of it would be different. It would probably not be as clear and as sharp. And it strikes me that that what these tools do for us is vast, but what they also demand of us is that we have all these look down experiences when at a concert, at a museum, you should be having a look up experience. You should be looking up unmediated. It doesn't mean you can't take a picture now and then.

Speaker 4:Right. If

Christine Rosen:you spend your whole time posing and filming and taking photos, you will not experience that memory wise. So when you try to recall it later, you're gonna have a different memory and not as not as clear and sharp a memory of that experience.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Yeah. Absolutely. And I just, but that goes back even before cell phones, so I'm also a big deadhead. I contain multitudes.

Tim Benson:But so there's always been you know? So, basically, the Grateful Dead allowed people to just tape their concerts, you know, whatever, like, that no problem with. And they actually set up, like, a back in the eighties, like, a specific taper section so that, like, all the tapers would be in one spot so they wouldn't be sticking their microphones up and blocking people's view and all that. And I think about, like, the tapers, all these guys that would just, like, go to every show and just, like, tape every show.

Speaker 4:Taping.

Tim Benson:And, like, so, thankfully, you know, we got all these tapes from these guys that got traded around, like, the whole ecosystem.

Speaker 4:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:But, like, I sort of felt I've always sort of felt bad for them because it's, like, they spent all their time, you know, making sure their taping gear was correct, and the levels were correct, and all this stuff, and the microphone placement was this and that. And, like, you're not really experiencing the show either. Like, you're making a document, and, like, you're doing a service, but, like, wouldn't you just, like, have more fun just hanging out and, you know?

Christine Rosen:Well and and you know what? If it's a small group of hobbyists and that's their thing, that's one thing. Yeah. We are all those guys now. We all spend more time creating information about our experiences than actually just having them.

Christine Rosen:Right? And the information in some ways becomes more valuable because it proves we had the experience rather than just saying, oh, yeah. I went to this concert. It was great. It's almost it's almost as if we need the reassurance of having documented it and having posted it on Instagram for people.

Christine Rosen:Not only for people to see that we did it, but for us to believe it was real.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Or for us to make other people think that we're interesting or Exactly. You know, I it's just I know I don't get that urge. Anyway, yeah. But there's something there seems to be some sort of, like, pushback to this in like, rears its head in, like, different places.

Tim Benson:Like, just for example, like, the, like, the rebirth of, like, vinyl records

Speaker 4:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:As like, which now outsell CDs. And all these kids buy vinyl even though I'm a CD guy. So even though vinyl is the audio quality is no better than CD or I mean, but aesthetically, as a package, it's obviously preferable. But, like and they'll spend, you know, $30 on the vinyl when they can just get it, you know, when they could just, you know, buy the MP threes for $10 or buy the CD for $12. But they want something I don't know.

Tim Benson:But maybe it's more of, like, the experience thing too because, like, there is something sort of romantic and sort of sexy about vinyl. Like, you drop the needle down on the

Christine Rosen:Well and it's it's the tangibility. The tangibility, that's a real thing. It's also it forces them to be to attend to the music in a way that even a CD, like, it'll play all the way through, but, like, record skip, you have to flip them to the b side. Like, there are all these sort of tactile interactions with the experience that don't exist if you're streaming music or or even with CDs. It's you still have to do some of that with CDs, but there is something about that interaction and the use of, like, I you have to do it yourself with your hand Yeah.

Speaker 4:Yeah.

Christine Rosen:That I think they crave because the rest of their world is doesn't have that. They do not do a lot with their hands. Like, how does they do their faces?

Tim Benson:No. And it's just, everything's sort of it's just back to Taylor Swift. I remember when the last album came out and, you know, streaming is now a metric for how they count sales or whatever, you know, what goes platinum or whatever or what is a, you know, top ten hit or whatnot. Right. And, I remember this headline going like, oh, Taylor Swift breaks Beatles record by having, like, like, 10 of the top 10 songs in the country.

Tim Benson:And, you know, and I was like, well, that's a little different because, like, when the Beatles had, like, the top 5 records in the country, like, you actually had to, like, go out of your house and Buy it. Physically go out and buy it and, like, you know, bring it back to your house. You didn't just, like, open your phone and play it Mhmm. And play it all the way through. And, like, it's you know, so it's not as an impressive feat to me that she had the top 10, you know, songs in the country at at one point when you don't really have to do anything nowadays to you know, it's a passive way of, like, showing that you, I mean, even if you just listen to the record once, someone like, oh, I hate this crap.

Tim Benson:You know? Like but if you're just listening to it. So that still counts, like, towards, like, Taylor Swift's part numbers. You know? That, like, that person who was just like, oh, let me give you the shot, who would never would have, like, in their 1000000 years gone out of their way to, like, go actually, like, down to the record store and, like, buy the record and bring it home and play it on a whim.

Tim Benson:Mhmm. Yeah. But there's, sorry. I'm sort of rambling about this.

Christine Rosen:No. I think but that you're you're talking about something that applies well beyond music. It's it's in every aspect of life. I think there's a craving, particularly in younger generations, to reintroduce friction in their lives, whether that's I have to leave the house to do this or I have to do this in person. You know, the the the trend among my son's friends for a while was when they'd all go out, they'd put everyone had to put their phones in the middle of the table and if you picked up whoever picked up their phone first, like, had to pay more.

Christine Rosen:The bill or, you know, they had all the

Tim Benson:Oh, nice. I like that.

Christine Rosen:They had to create these strategies because they know how it's like a siren song they can't resist. So they they create a strategy to prevent themselves, you know, to kind of block themselves from doing the easy thing because they want a little friction in their lives. It's good for I mean, it's good for us as human beings to have to overcome obstacles and and certain proclivities. Makes us better people.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Oh, man. I'm already running out of time. So much stuff I wanted to get through, but I think maybe this, I I guess we should talk about it. I don't know.

Speaker 4:Uh-oh. This sounds ominous.

Tim Benson:So one thing that I think is, like, really more so than, like, other things. Problem has really problematically changed people is the ubiquity of porn.

Christine Rosen:Oh, yeah.

Tim Benson:And, not that I'm like a, you know, a career who's never looked at porn before or anything like that, but, like, it seems to be and I I don't really wanna get my personal details, but it seems to be that it is changing the way people, make love

Speaker 4:to each other.

Tim Benson:You know?

Christine Rosen:Yeah. No. Absolute no. There's there's actual data on all of this. So no.

Christine Rosen:No. It it it has transformed not only people's own perception of their sexual appeal and their sexual proclivities, it has transformed the way they understand what sex even is. And that's what fascinated me. I have my only regret in writing this because I've had this conversation now many times. Why didn't I talk more about porn?

Christine Rosen:But I did. Like, I have a whole section of a chapter about how we mediate pleasure. But it it is a huge subject because it is it is something that, in in a weird way, porn turns sex into a machine like thing. Right? It's like you do this, you do this, there's a formula every and you know what?

Christine Rosen:We're hardwired to wanna see people have sex. Like our brains are like, oh, that's fun. Let's see more of that. What the what porn online delivers is just a constant stream and so there is the problem is

Tim Benson:that It's way weirder.

Christine Rosen:It's gets weirder because there's a there's a the our as our reaction went small and there's no look. It used to be if you had a weird proclivity, you had to go seek it out in a dark alley and find that one

Tim Benson:weird magazine. Go down to the weird porno movie theater and

Christine Rosen:sit there with the Scumble in, grab

Speaker 4:your video and run out. Yeah.

Christine Rosen:No. But the the thing that that and and that did bring a lot of shame to people, and I'm not not a shamer. But what it also did is really make you really had to wanna see it. And the thing now is that it it it it's lost any titillation value in a sense. It just becomes this way.

Christine Rosen:And and what worries me, particularly for young men, is that their expectations are such. And and if they start at a really young

Speaker 4:age, they

Christine Rosen:don't they can't actually get aroused by an actual human being in front of them.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Oh, but the other thing is too and I really don't know how to talk about this without sounding like a skis. But I've noticed in my own personal experience so, the women my age compared to, say, women who are you know, once I got into my into my thirties and there was, like, at some points, a significant age gap

Christine Rosen:Mhmm.

Tim Benson:Between the two parties

Speaker 4:Yes.

Tim Benson:The younger women, were way more horny in how

Speaker 4:They're mimic they see.

Tim Benson:Right. Right. And it was just like, it was

Christine Rosen:just like happier or more satisfied.

Tim Benson:But it was just like that they, like, just thought that this was, like, what sex was.

Christine Rosen:Yeah.

Tim Benson:And,

Christine Rosen:But it is for

Tim Benson:their kids. Into yeah.

Christine Rosen:No. It I mean, this but this this is actually so when people worry about social media and how it, you know, changes people's personalities, and they should worry in the same way, you know, without judgment about what people wanna do with their time when they when they go to look for porn, it turns sex, which should be this weird, dangerous slightly dangerous, kind of awesome, unique thing where you really wanna find someone who gets what you like and vice versa, it turns it into this performance for everyone. Everyone performs a role or is expected to or thinks that that's what sex is. And so it again, it's very homogenizing. And I when I talk to some of my younger students, that's their complaint.

Christine Rosen:They're like, well, I have to give them the porn star experience, and and I guess that's what I should like too because that's what everybody does.

Speaker 4:And I'm

Christine Rosen:like, you don't even know what you like because you've just been fed a steady diet

Tim Benson:and whatever you want. So it's like no wonder when you see all, like, these, like, surveys and data trends over there that, like, kids aren't having sex like they

Christine Rosen:used to.

Tim Benson:They're just like, what's going on with, like, the kids?

Christine Rosen:Like, you know They have all these vicarious

Tim Benson:so lame, and it's like, well, you know, maybe they're not having sex as much because they don't like it because it's so Right. Again, mechanical and porny and weird.

Christine Rosen:I don't think they really know what good sex is. That's my concern. Not that I'm gonna take over Ruth doctor Ruth's mantle. Although that would be a fun second career for me, but I gotta be older to do that. Yeah.

Speaker 5:10 years

Speaker 4:from now.

Tim Benson:Alright. So off of porn. That's enough. So oh, here. Just wrapping up, I guess, because we gotta go in a little bit.

Tim Benson:Just, the difference, between places and spaces and, you know, the the transformation of public space by mobile technology and how that is affecting our our social bonds or communal bonds, you know, neighborhood bonds, those sort of things. What is the difference between the 2, and and how is mobile technology changing that?

Christine Rosen:So this is something that's, bugged me since cell phone use became ubiquitous. I live in a city. I live in Washington DC. I walk a lot. I take a lot of mass transit.

Christine Rosen:I also spend a lot of time in New York. And I note I really did notice a change, not just in how people go about, behaving in public space, but our expectations of each other. So when you have a cell phone and you can tune everybody else out, you don't really care what's going on around you. And if something dramatic happens like a fight breaks out, nowadays people are far more likely not to step in or call for help, but to film it.

Tim Benson:They film it. Yeah.

Christine Rosen:They film it. And that sort of there's it's turned us all into these kind of weird bystanders to life. Right? And and we think we're doing something because we're we're doing something we're engaging with our phone, but that's not doing what we owe each other as human beings. And this is a small there there's fascinating behavioral science research about, how does someone feel when you step into an elevator and you don't make brief eye contact with them or that little nod or if you bump into someone on the street, both people are supposed to go, oh, hey.

Christine Rosen:Sorry. That diffuses the situation. All of these little unspoken rules of social behavior, they're not exactly hardwired, but they are a thing we do without thinking about it. Now those rules are out the window, and we are running into each other and getting really angry and impatient and difficult. It's why we have air rage and road rage rates that are through the roof.

Christine Rosen:We don't know how to behave because we can constantly remove ourselves from public space or we can remove ourselves from places in public and go into our cyberspace worlds and that's the place space place is is bounded in physical space and has rules. You're in a place, there are rules for how to behave, some of them are intuitive, some of them are are not, like, no shirt, you know, beaches, no shirt, no shoes, no service. This was, like, my childhood, every every every shop had this in the window. If you're from Florida, you get it. If you don't, you don't.

Christine Rosen:But that's like

Tim Benson:It's not a hard and fast rule.

Christine Rosen:Exactly. I know. I know. Rarely enforced, actually, after a certain hour of the day. But it is but those sorts of rules are are there not to not to control us, but to help us get along with people we don't know, particularly in cities.

Christine Rosen:And I spent a lot of time observing people interacting in these public spaces, and it has changed dramatically.

Tim Benson:No. I mean, I just remember when, like, the iPad first became sort of ubiquitous

Speaker 4:and you

Tim Benson:had the headphones and stuff. And I remember the first time I was in the city, I was in Manhattan, on the subway, and just seeing people with

Christine Rosen:the iPad.

Tim Benson:And I'm just like, really? Like, you like, it's a subway. Like, you you keep your head on swivel.

Christine Rosen:Kind of looker. Yes.

Tim Benson:Yeah. You know what I mean? Like like Awareness. Yeah. Or just people walking down the the street in Manhattan just with the phone you know, the headphones in and, like, I'd worry about getting mugged.

Tim Benson:But, you know, that's a different time in New York. But, yeah, too. And another thing, I don't know if, because I know people still, like, go out and socialize and Mhmm. Like, talk to their neighbors and things like that. One thing I've noticed I don't know.

Tim Benson:Talk to their neighbors and things like that. One thing I've noticed I don't know if this is really a technological change or anything, but, like, dinner parties. Like, I don't know. Maybe it's just, like, my friend group or something. Like, we're just all Florida degenerates or whatever.

Tim Benson:But, like, like, I like, when I was a kid, I remember, like, my parents have dinner parties, and they dress up and, like, you have cocktails and the adults and, like, you couldn't hang out because this was adult time.

Christine Rosen:Exactly.

Speaker 4:And

Tim Benson:if you were gonna hang out, like, you couldn't, like, say anything stupid. You just, like, you just shut up and listen to adult time and adult talk and all that stuff, and, you know, back when people smoked in the house and all that stuff.

Speaker 4:And,

Tim Benson:but I was thinking, like, I was like, you know what? Like, I don't think any one of my friends and I was like, I know I haven't, like, has never, like, thrown, like, a dinner party, you know, just like cocktails and hors d'oeuvres and, like, everybody goes and sits down and chats and stuff. Like, we go out to eat all the time and then, you know, and go to restaurants and do that thing. But, like

Christine Rosen:That's different.

Tim Benson:Or, like, or, like, barbecues or, like, you know, people come over for the Super Bowl or something like that. But, like, the the whole like, the dinner party phenomena, I don't know if it's just me and my, like, my group or if it's something that's but I just feel like that's a, like, a lost art that's completely, like, gone away. Maybe

Christine Rosen:It it I mean, I data on in person gathering shows that people are having far fewer of them across the board and in in most age groups. And they are, part of that is because they don't feel the need to connect in person as much and don't want to, and it's a pain. The difference what dinner parties are though, and I'll say I've been in DC since 1995, there used to be a lot more of them. When I first came here, I knew hardly anyone. When I would get invited to the opening of an envelope, I'm like, I better go.

Christine Rosen:I gotta meet some people. I don't know anyone here. But they I met people from all across the political spectrum here. And this is a this is a government town and a political town. And, you know, fast forward 30 years, and I'm I have friends, you know, who've worked in Republican administrations, Democratic administrations.

Christine Rosen:And we one of the ways that we all understand each other is that when you people you invite people into your home, everyone has to be civil. You have a common conversation. And when things get tense, you know, the host or hostess is like, oh, okay. Well, we all disagree. Let's wait.

Christine Rosen:There there's a civility that's imposed because of the the, the way you're getting together, which is different from a barbecue, different from a pool bar.

Speaker 4:You know,

Christine Rosen:there are all these other great ways to get together and people should do that. But what I think you're you're touching on here is that lack of the the civility at that very basic level at the small, community neighborhood level. If we're not doing that, it makes it harder to be civil, on the broad in the broader political side.

Tim Benson:And there's an intimacy to the dinner party that, like, again, you don't get it like a pool party or barbecue or anything like that. And I always thought, like, this would never happen. I was like, well, you know, if I ran for congress, say I got elected to congress, you know, what would I do to, like, try to, you know, lower the temperature between Yeah. Because everyone's just, you know, at each other's throats, and they all fucking hate each other. And I was like, I would try to, like, invite, like, every single member of congress, like or as many as possible.

Tim Benson:I don't know. You know?

Christine Rosen:You don't want all those guys and gals in your house.

Tim Benson:Got as many as possible. Like, like, just, you know, over to, like, have dinner and Yes. Talk and, like, you know, just get get to know each other, like, on a personal level outside of, like, politics and, you know, talk about you know? So where'd you grow up? You know, you know, what did your parent you know, what did your family do?

Tim Benson:And blah blah blah. You know? Just humanize people that I don't think, I don't know. Trust. Yeah.

Tim Benson:Yeah. Exactly.

Christine Rosen:And we're lacking trust now in

Tim Benson:our Right. So that maybe, like, you know, we can lower the stakes in the house. We may not, you know, maybe not knife each other. I mean, it's politics that's gonna happen, but maybe this is all, you know, naive of me. But, I feel like something like that could help.

Tim Benson:Maybe they should make it a law that, like, conflicts

Speaker 4:with you.

Tim Benson:Anyway, alright. So we've gone long enough. The

Speaker 4:You've had enough.

Tim Benson:No. No. No. I mean, there's lots of stuff we could talk about, but I I said I'd only keep you in hours. I'm not gonna keep you longer than that.

Tim Benson:But, so I guess normal exit question again, entry and exit questions, for everyone that comes on. You know, basically, what would you want the audience to get out of this book, or what's the one thing you'd want a reader to take away from it having having read it?

Christine Rosen:What I hope people will take away from it is, an awareness that they now have to actively choose those human experiences, whether that's writing something by hand, which will feel weird the first few times you do it, whether that's not picking up your phone when you're at a red light in your car, whether that's, you know, reaching out and seeing a friend in person when it's much easier to just, like, text them. You have to actively choose those human interactions. And if you do, I think you'll notice a difference in the quality of your experiences overall. It's not always possible to do that. I understand that.

Christine Rosen:But we have to now actively choose that. And if we do, I think we have a more, more hopeful way of moving back to human centered activities, and those are gonna become more important in the in the AI era.

Tim Benson:Alright. Well, very well said. Well, once again, the name of the book is The Extinction of Experience Being Human in a Disembodied World. Fantastic, fantastic book. And not because I'm also sort of a quasi Luddite in part.

Tim Benson:No. But it's just a really interesting look at at how what we're in danger of losing as technology, becomes more and more ubiquitous in our life, especially with, you know, coming of AI and all that stuff, and so much to worry about with that. But it's a wonderful defense of reality and of being human and corporal. I highly, highly recommend it to everybody out there. Again, the name of the book is The Extinction of Being Human in a Disembodied World.

Tim Benson:The author, Christine Rosen, Doctor. Christine Rosen. I'm gonna say it again. Too bad. So, Christine, thank you so, so much for coming on the podcast and talking about your book with us.

Tim Benson:And thank you so much for actually taking the time out of your life to write the thing so that we all could, enjoy the the fruits of your labor.

Christine Rosen:Well, thank you so much. I really enjoyed the conversation.

Tim Benson:Oh, no problem. Thank you. And again, if you like this podcast, please consider leaving us a 5 star review and sharing with your friends. And if, you have any questions or comments or there's any books out there you'd like to recommend to the podcast, you can always reach out to me at tbenson@heartland.org. That's t b e n s o n@heartland.org.

Tim Benson:And for more information about the Heartland Institute, you can just go to heartland.org. What else? Oh, yeah. We have our Twitter slash x account. You can always reach out to us there too, at illbooks@illbooks.

Tim Benson:So make sure you check that out. You know? Follow us and all that stuff. Yeah. That's pretty much it, though.

Tim Benson:So, thanks for listening, everybody. We'll see you guys next time. Take care. Love you, Robbie. Love you, mom.

Tim Benson:Bye bye.

Speaker 5:As I walk through the valley where I harvest my grain, I take a look at my wife and realize she's very plain. But that's just perfect for an Amish like me. You know I shun fancy things like electricity. At 4:30 in the morning, I'm milking cows. Jebediah feeds the chickens and Jacob plows.

Speaker 5:Fool, I've been milking and plowing so long that even Ezekiel thinks that my mind is gone. I'm a man of the land, I'm into discipline. Got a Bible in my hand and a beard on my chin. But if I finish all of my chores and you finish dying, then tonight we're gonna party like it's 16/99. We've been spending most our lives living in an Amish paradise.

Speaker 5:I churn butter once or twice living in an Amish A local boy kicked me in the butt last week. I just smiled at him, and I turned the other cheek. I really don't care. In fact, I wish him well, because I'll be laughing my head off when he's burning in hell. But I ain't never punched a tourist even if he deserved it.

Speaker 5:An Amish with a 2, you know that's unheard of. I never wear buttons but I got a cool hat and my homies agree I really look good in black, fool. If you come to visit you'll be bored to tears. We haven't even paid the phone bill in 300 years. But we ain't really quaint, so please don't point and stare.

Speaker 5:We're just technologically impaired. There's no phone, no lights, no motor car, not a single luxury. Like Robinson Crusoe, it's as primitive as can be. We've been spending most our lives living in an Irish paradise. Hitching up the buggy, churning lots of butter, raise the barn on Monday, soon I'll raise another.

Speaker 5:Think you're really righteous? Think you're pure in heart? Well, I know I'm a 1000000 times as humble as thou art. I'm the pious guy the little omelettes wanna be like on my knees day and night, scoring points for the afterlife. So don't be vain and don't be whiny, or else my brother, I might have to get medieval on your hiney.

Speaker 5:Paradise. We're all crazy men in the night living

Speaker 4:in an Amish paradise. There's no concert traffic lights

Speaker 5:living in an Amish

Creators and Guests